Sustainable development and equity provide a basis for assessing climate policies. Limiting the effects of climate change is necessary to achieve sustainable development and equity, including poverty eradication. Countries’ past and future contributions to the accumulation of GHGs in the atmosphere are different, and countries also face varying challenges and circumstances and have different capacities to address mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation and adaptation raise issues of equity, justice and fairness and are necessary to achieve sustainable development and poverty eradication. Many of those most vulnerable to climate change have contributed and contribute little to GHG emissions. Delaying mitigation shifts burdens from the present to the future, and insufficient adaptation responses to emerging impacts are already eroding the basis for sustainable development. Both adaptation and mitigation can have distributional effects locally, nationally and internationally, depending on who pays and who benefits. The process of decision-making about climate change, and the degree to which it respects the rights and views of all those affected, is also a concern of justice. {WG II 2.2, 2.3, 13.3, 13.4, 17.3, 20.2, 20.5, WG III SPM.2, 3.3, 3.10, 4.1.2, 4.2, 4.3, 4.5, 4.6, 4.8}

Effective mitigation will not be achieved if individual agents advance their own interests independently. Climate change has the characteristics of a collective action problem at the global scale, because most GHGs accumulate over time and mix globally, and emissions by any agent (e.g., individual, community, company, country) affect other agents. Cooperative responses, including international cooperation, are therefore required to effectively mitigate GHG emissions and address other climate change issues. The effectiveness of adaptation can be enhanced through complementary actions across levels, including international cooperation. The evidence suggests that outcomes seen as equitable can lead to more effective cooperation. {WG II 20.3.1, WG III SPM.2, TS.1, 1.2, 2.6, 3.2, 4.2, 13.2, 13.3}

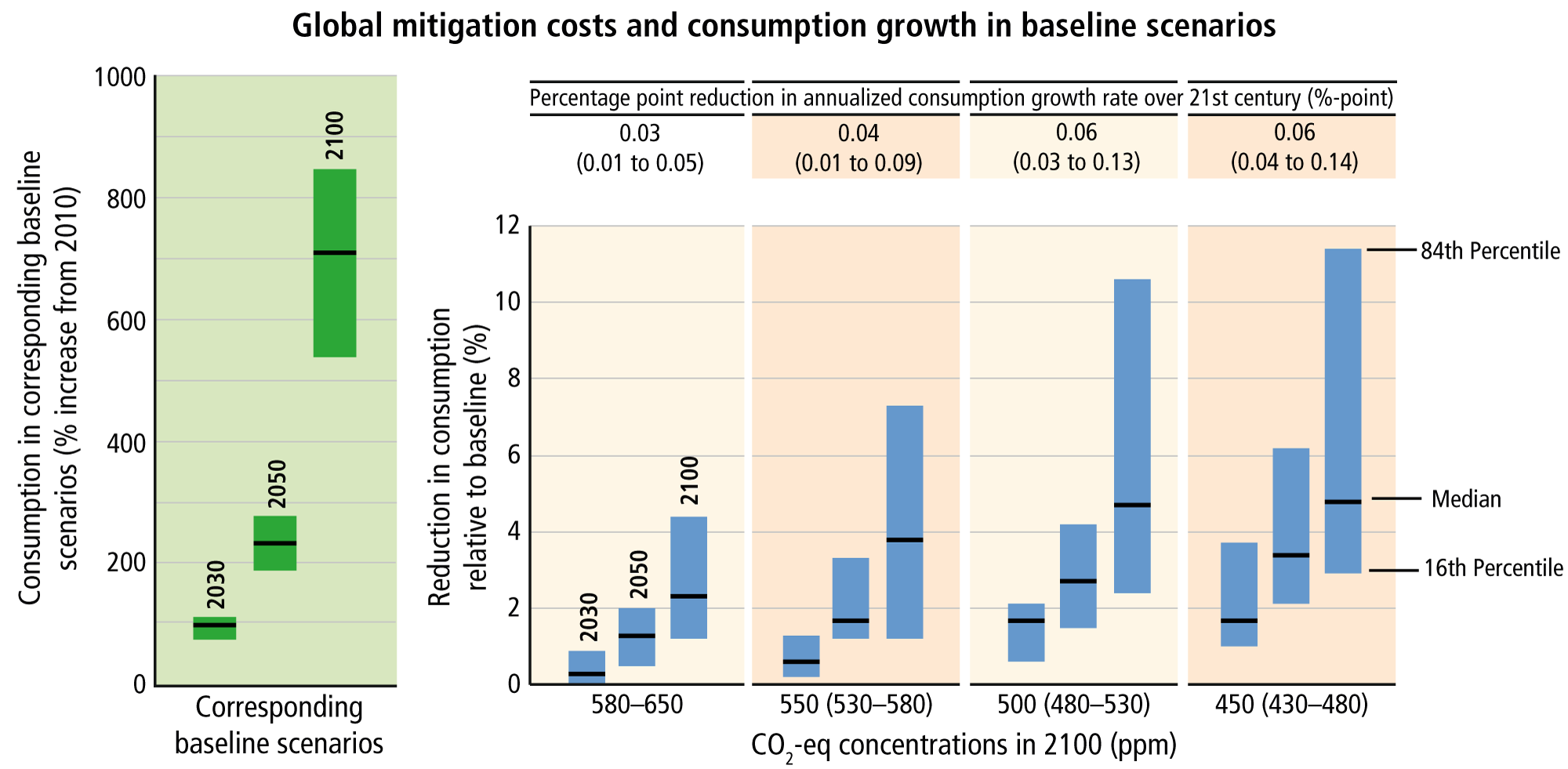

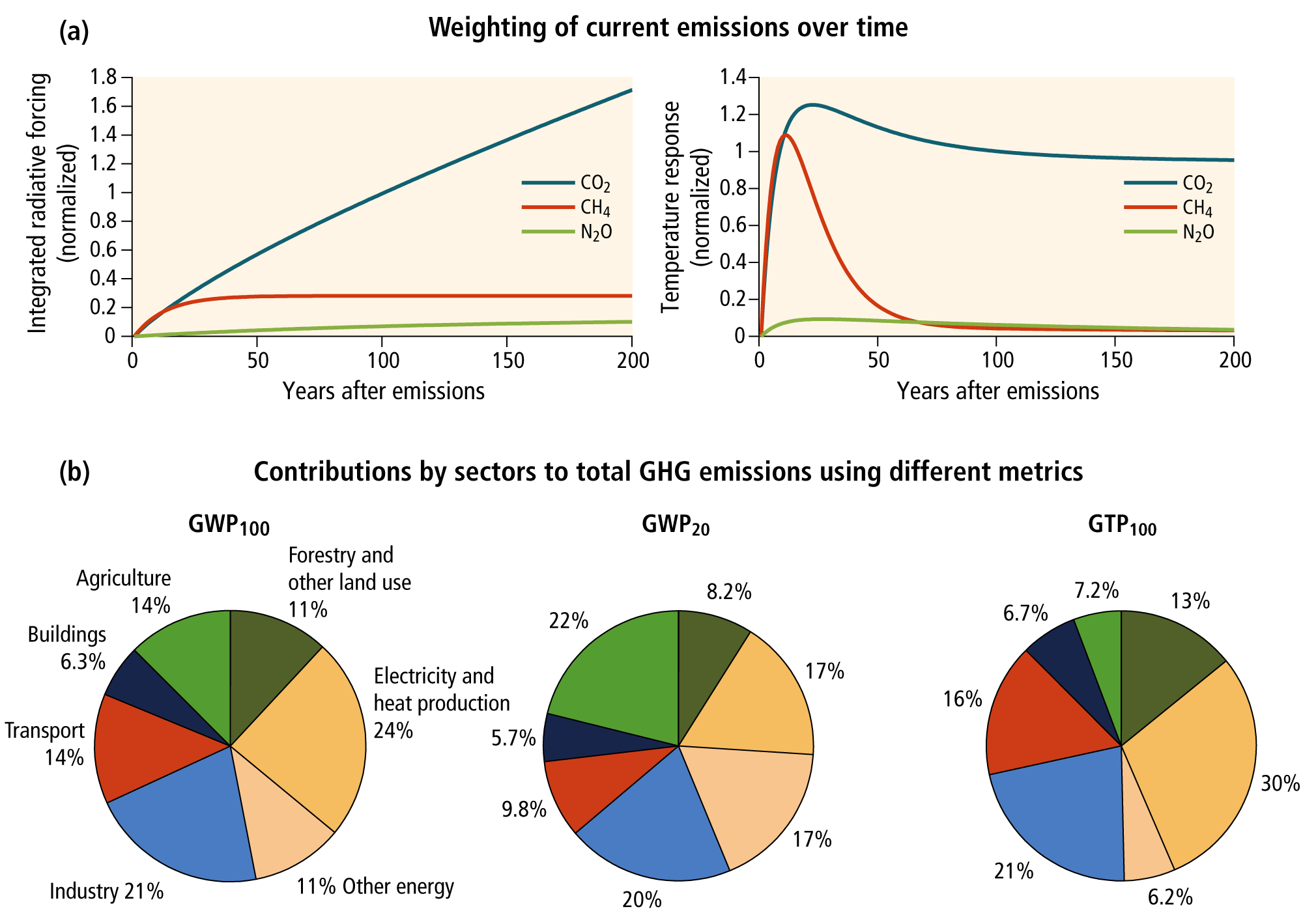

Decision-making about climate change involves valuation and mediation among diverse values and may be aided by the analytic methods of several normative disciplines. Ethics analyses the different values involved and the relations between them. Recent political philosophy has investigated the question of responsibility for the effects of emissions. Economics and decision analysis provide quantitative methods of valuation which can be used for estimating the social cost of carbon (see Box 3.1), in cost–benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses, for optimization in integrated models and elsewhere. Economic methods can reflect ethical principles, and take account of non-marketed goods, equity, behavioural biases, ancillary benefits and costs and the differing values of money to different people. They are, however, subject to well-documented limitations. {WG II 2.2, 2.3, WG III SMP 2, Box TS.2, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6, 3.2-3.6, 3.9.4}

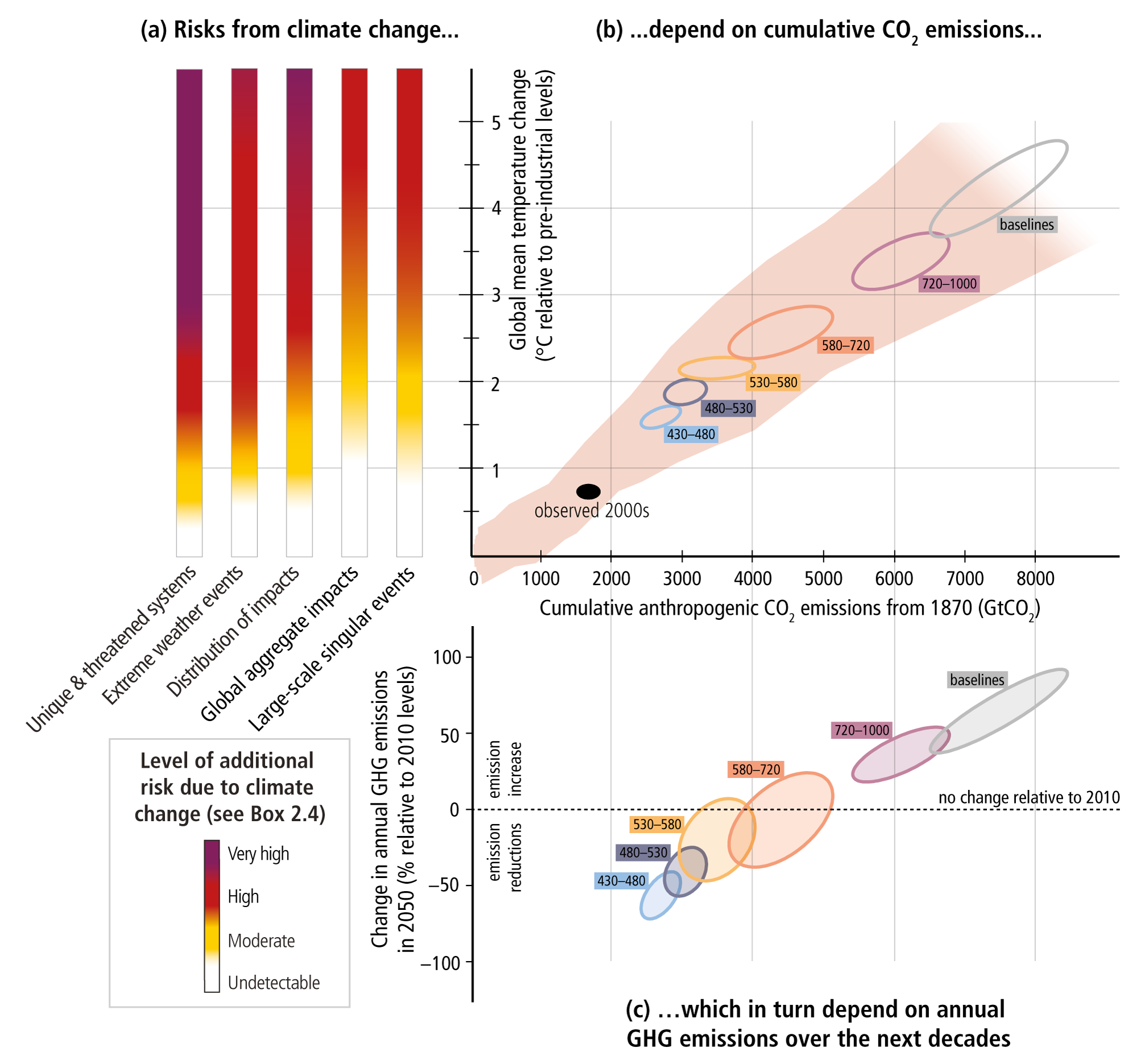

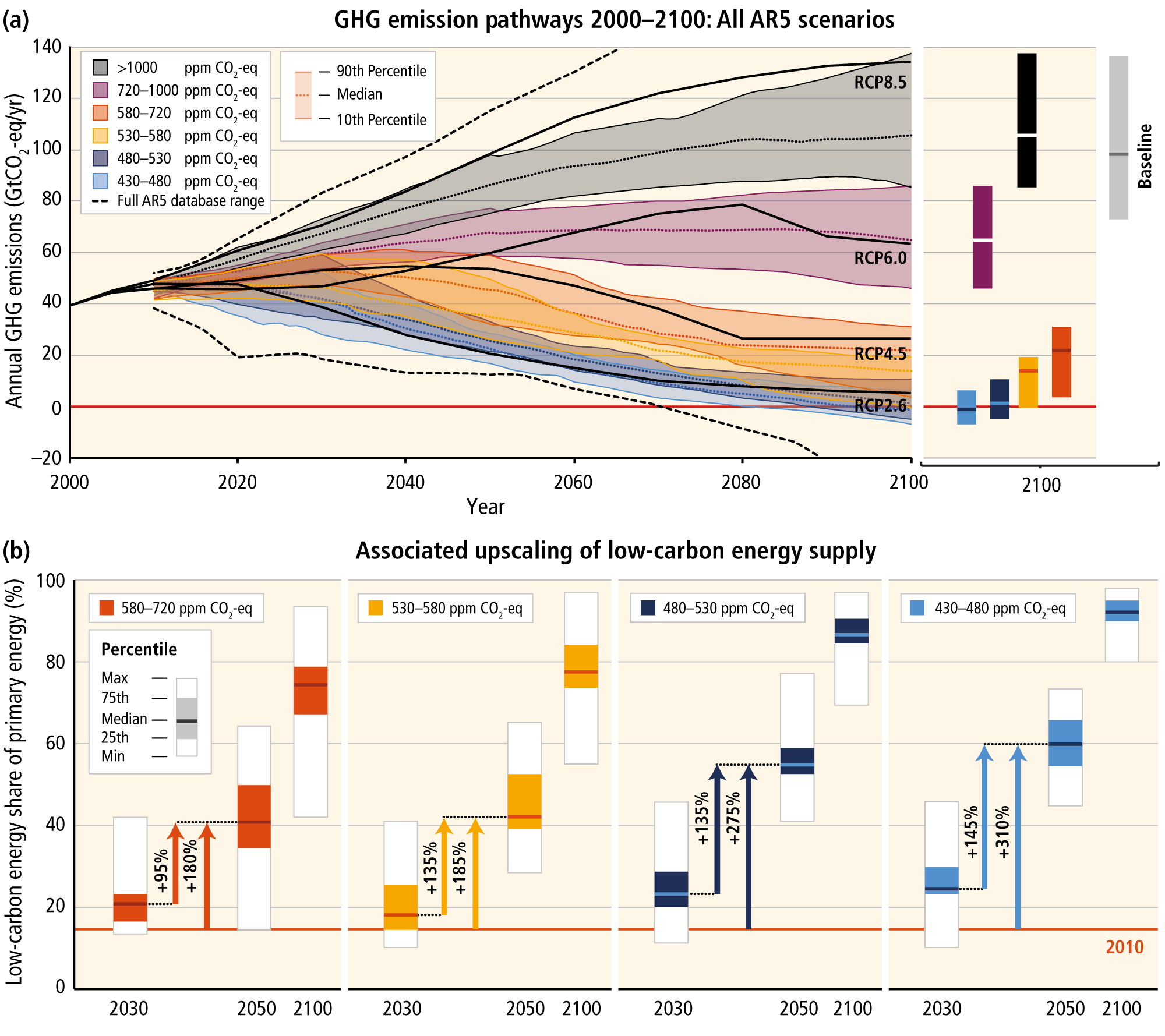

Analytical methods of valuation cannot identify a single best balance between mitigation, adaptation and residual climate impacts. Important reasons for this are that climate change involves extremely complex natural and social processes, there is extensive disagreement about the values concerned, and climate change impacts and mitigation approaches have important distributional effects. Nevertheless, information on the consequences of emissions pathways to alternative climate goals and risk levels can be a useful input into decision-making processes. Evaluating responses to climate change involves assessment of the widest possible range of impacts, including low-probability outcomes with large consequences. {WG II 1.1.4, 2.3, 2.4, 17.3, 19.6, 19.7, WG III 2.5, 2.6, 3.4, 3.7, Box 3-9}

Effective decision-making and risk management in the complex environment of climate change may be iterative: strategies can often be adjusted as new information and understanding develops during implementation. However, adaptation and mitigation choices in the near term will affect the risks of climate change throughout the 21st century and beyond, and prospects for climate-resilient pathways for sustainable development depend on what is achieved through mitigation. Opportunities to take advantage of positive synergies between adaptation and mitigation may decrease with time, particularly if mitigation is delayed too long. Decision-making about climate change is influenced by how individuals and organizations perceive risks and uncertainties and take them into account. They sometimes use simplified decision rules, overestimate or underestimate risks and are biased towards the status quo. They differ in their degree of risk aversion and the relative importance placed on near-term versus long-term ramifications of specific actions. Formalized analytical methods for decision-making under uncertainty can account accurately for risk, and focus attention on both short- and long-term consequences. {WG II SPM A-3, SPM C-2, 2.1-2.4, 3.6, 14.1-14.3, 15.2-15.4, 17.1-17.3, 17.5, 20.2, 20.3, 20.6, WG III SPM.2, 2.4, 2.5, 5.5, 16.4}

Edit