207

3

Social, Economic, and Ethical

Concepts and Methods

Coordinating Lead Authors:

Charles Kolstad (USA), Kevin Urama (Nigeria / UK / Kenya)

Lead Authors:

John Broome (UK), Annegrete Bruvoll (Norway), Micheline Cariño Olvera (Mexico), Don

Fullerton (USA), Christian Gollier (France), William Michael Hanemann (USA), Rashid Hassan

(Sudan / South Africa), Frank Jotzo (Germany / Australia), Mizan R. Khan (Bangladesh), Lukas Meyer

(Germany / Austria), Luis Mundaca (Chile / Sweden)

Contributing Authors:

Philippe Aghion (USA), Hunt Allcott (USA), Gregor Betz (Germany), Severin Borenstein (USA),

Andrew Brennan (Australia), Simon Caney (UK), Dan Farber (USA), Adam Jaffe (USA / New

Zealand), Gunnar Luderer (Germany), Axel Ockenfels (Germany), David Popp (USA)

Review Editors:

Marlene Attzs (Trinidad and Tobago), Daniel Bouille (Argentina), Snorre Kverndokk (Norway)

Chapter Science Assistants:

Sheena Katai (USA), Katy Maher (USA), Lindsey Sarquilla (USA)

This chapter should be cited as:

Kolstad C., K. Urama, J. Broome, A. Bruvoll, M. Cariño Olvera, D. Fullerton, C. Gollier, W. M. Hanemann, R. Hassan, F. Jotzo,

M. R. Khan, L. Meyer, and L. Mundaca, 2014: Social, Economic and Ethical Concepts and Methods. In: Climate Change

2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovern-

mental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler,

I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)].

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

208208

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

Contents

Executive Summary � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 211

3�1 Introduction � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 213

3�2 Ethical and socio-economic concepts and principles � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 214

3�3 Justice, equity and responsibility � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 215

3�3�1 Causal and moral responsibility

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 215

3�3�2 Intergenerational justice and rights of future people

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 216

3�3�3 Intergenerational justice: distributive justice

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 216

3�3�4 Historical responsibility and distributive justice

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 217

3�3�5 Intra-generational justice: compensatory justice and historical responsibility

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 217

3�3�6 Legal concepts of historical responsibility

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 218

3�3�7 Geoengineering, ethics, and justice

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 219

3�4 Values and wellbeing � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 220

3�4�1 Non-human values

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 220

3�4�2 Cultural and social values

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 221

3�4�3 Wellbeing

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 221

3�4�4 Aggregation of wellbeing

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 221

3�4�5 Lifetime wellbeing

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 222

3�4�6 Social welfare functions

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 222

3�4�7 Valuing population

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 223

3�5 Economics, rights, and duties � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 223

3�5�1 Limits of economics in guiding decision making

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 224

209209

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

3�6 Aggregation of costs and benefits � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 225

3�6�1 Aggregating individual wellbeing

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 225

3.6.1.1 Monetary values

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

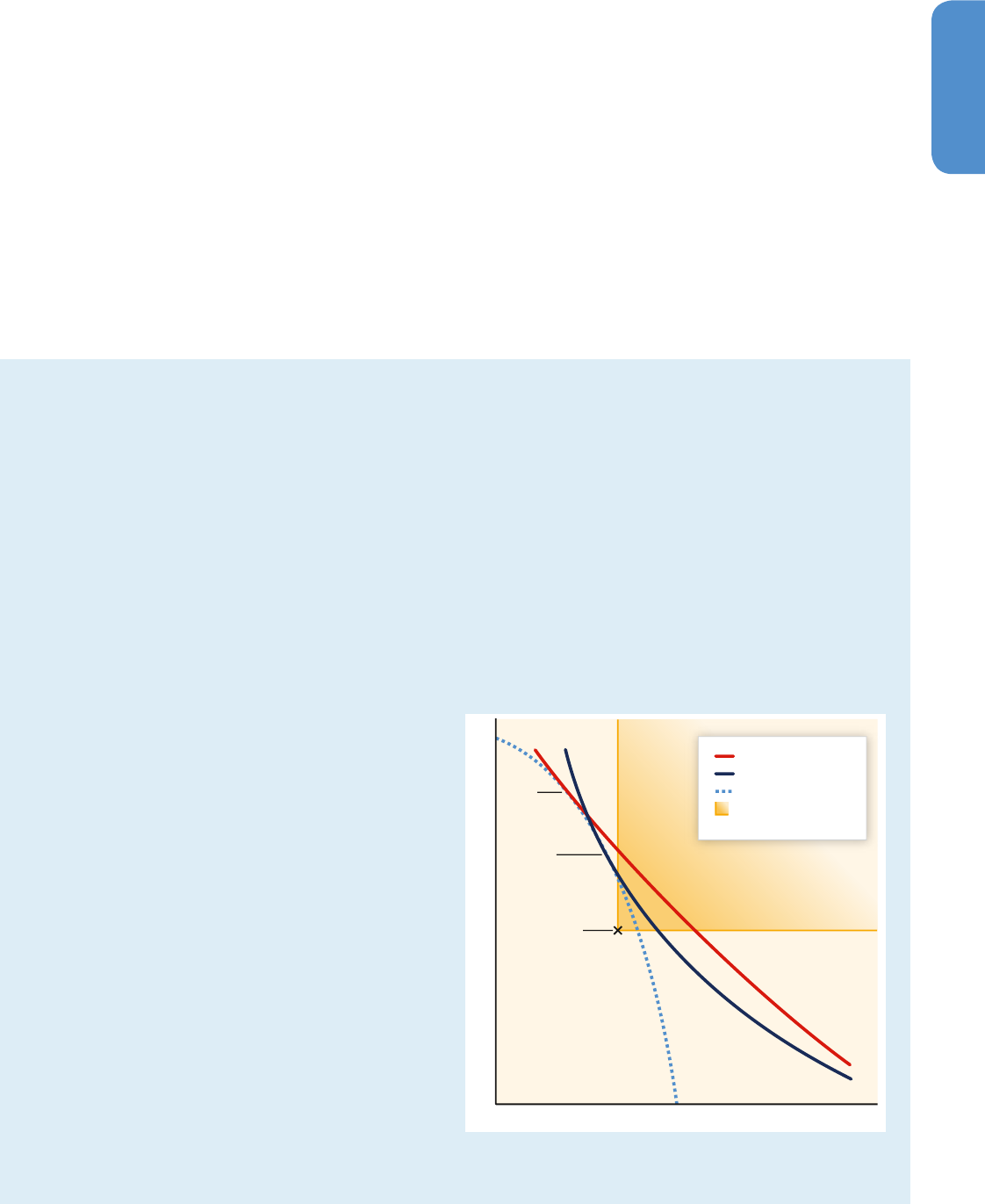

3�6�2 Aggregating costs and benefits across time

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 228

3�6�3 Co-benefits and adverse side-effects

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 232

3.6.3.1 A general framework for evaluation of co-benefits and adverse side-effects

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232

3.6.3.2 The valuation of co-benefits and adverse side-effects

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 233

3.6.3.3 The double dividend hypothesis

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234

3�7 Assessing methods of policy choice � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 235

3�7�1 Policy objectives and evaluation criteria

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 235

3.7.1.1 Economic objectives

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

3.7.1.2 Distributional objectives

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

3.7.1.3 Environmental objectives

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

3.7.1.4 Institutional and political feasibility

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 237

3�7�2 Analytical methods for decision support

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 238

3.7.2.1 Quantitative-oriented approaches

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 238

3.7.2.2 Qualitative approaches

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

3�8 Policy instruments and regulations � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 239

3�8�1 Economic incentives

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 239

3.8.1.1 Emissions taxes and permit trading

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

3.8.1.2 Subsidies

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

3�8�2 Direct regulatory approaches

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 240

3�8�3 Information programmes

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 241

3�8�4 Government provision of public goods and services, and procurement

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 241

3�8�5 Voluntary actions

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 241

3�8�6 Policy interactions and complementarity

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 241

3�8�7 Government failure and policy failure

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 241

3.8.7.1 Rent-seeking

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

3.8.7.2 Policy uncertainty

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

3�9 Metrics of costs and benefits � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 242

3�9�1 The damages from climate change

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 243

3�9�2 Aggregate climate damages

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 245

210210

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

3�9�3 The aggregate costs of mitigation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 247

3�9�4 Social cost of carbon

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 249

3�9�5 The rebound effect

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 249

3�9�6 Greenhouse gas emissions metrics

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 250

3�10 Behavioural economics and culture � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 252

3�10�1 Behavioural economics and the cost of emissions reduction

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 252

3.10.1.1 Consumer undervaluation of energy costs

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

3.10.1.2 Firm behaviour

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

3.10.1.3 Non-price interventions to induce behavioural change

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

3.10.1.4 Altruistic reductions of carbon emissions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

3.10.1.5 Human ability to understand climate change

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

3�10�2 Social and cultural issues

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 254

3.10.2.1 Customs

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

3.10.2.2 Indigenous peoples

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

3.10.2.3 Women and climate change

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

3.10.2.4 Social institutions for collective action

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 255

3�11 Technological change � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 256

3�11�1 Market provision of TC

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 256

3�11�2 Induced innovation

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 256

3�11�3 Learning-by-doing and other structural models of TC

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 257

3�11�4 Endogenous and exogenous TC and growth

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 257

3�11�5 Policy measures for inducing R&D

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 257

3�11�6 Technology transfer (TT)

� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 257

3�12 Gaps in knowledge and data � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 258

3�13 Frequently Asked Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 259

References � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 260

211211

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

Executive Summary

This framing chapter describes the strengths and limitations of the

most widely used concepts and methods in economics, ethics, and

other social sciences that are relevant to climate change. It also pro-

vides a reference resource for the other chapters in the Intergovern-

mental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5),

as well as for decision makers.

The significance of the social dimension and the role of ethics and

economics is underscored by Article 2 of the United Nations Frame-

work Convention on Climate Change, which indicates that an ultimate

objective of the Convention is to avoid dangerous anthropogenic inter-

ference with the climate system. Two main issues confronting society

(and the IPCC) are: what constitutes ‘dangerous interference’ with the

climate system and how to deal with that interference. Determining

what is dangerous is not a matter for natural science alone; it also

involves value judgements — a subject matter of the theory of value,

which is treated in several disciplines, including ethics, economics, and

other social sciences.

Ethics involves questions of justice and value. Justice is concerned with

equity and fairness, and, in general, with the rights to which people

are entitled. Value is a matter of worth, benefit, or good. Value can

sometimes be measured quantitatively, for instance, through a social

welfare function or an index of human development.

Economic tools and methods can be used in assessing the positive

and negative values that result from particular decisions, policies, and

measures. They can also be essential in determining the mitigation

and adaptation actions to be undertaken as public policy, as well as

the consequences of different mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Economic tools and methods have strengths and limitations, both of

which are detailed in this chapter.

Economic tools can be useful in designing climate change miti-

gation policies (very high confidence). While the limitations of eco-

nomics and social welfare analysis, including cost-benefit analysis, are

widely documented, economics nevertheless provides useful tools for

assessing the pros and cons of taking, or not taking, action on climate

change mitigation, as well as of adaptation measures, in achieving

competing societal goals. Understanding these pros and cons can help

in making policy decisions on climate change mitigation and can influ-

ence the actions taken by countries, institutions and individuals. [Sec-

tion 3.2]

Mitigation is a public good; climate change is a case of ‘the

tragedy of the commons’ (high confidence). Effective climate change

mitigation will not be achieved if each agent (individual, institution or

country) acts independently in its own selfish interest, suggesting the

need for collective action. Some adaptation actions, on the other hand,

have characteristics of a private good as benefits of actions may accrue

more directly to the individuals, regions, or countries that undertake

them, at least in the short term. Nevertheless, financing such adaptive

activities remains an issue, particularly for poor individuals and coun-

tries. [3.1, 3.2]

Analysis contained in the literature of moral and political phi-

losophy can contribute to resolving ethical questions that are

raised by climate change (medium confidence). These questions

include how much overall climate mitigation is needed to avoid ‘dan-

gerous interference’, how the effort or cost of mitigating climate

change should be shared among countries and between the present

and future, how to account for such factors as historical responsibility

for emissions, and how to choose among alternative policies for miti-

gation and adaptation. Ethical issues of wellbeing, justice, fairness, and

rights are all involved. [3.2, 3.3, 3.4]

Duties to pay for some climate damages can be grounded in

compensatory justice and distributive justice (medium confi-

dence). If compensatory duties to pay for climate damages and adap-

tation costs are not due from agents who have acted blamelessly,

then principles of compensatory justice will apply to only some of

the harmful emissions [3.3.5]. This finding is also reflected in the pre-

dominant global legal practice of attributing liability for harmful emis-

sions [3.3.6]. Duties to pay for climate damages can, however, also be

grounded in distributive justice [3.3.4, 3.3.5].

Distributional weights may be advisable in cost-benefit analysis

(medium confidence). Ethical theories of value commonly imply that

distributional weights should be applied to monetary measures of ben-

efits and harms when they are aggregated to derive ethical conclu-

sions [3.6.1]. Such weighting contrasts with much of the practice of

cost-benefit analysis.

The use of a temporal discount rate has a crucial impact on the

evaluation of mitigation policies and measures� The social dis-

count rate is the minimum rate of expected social return that com-

pensates for the increased intergenerational inequalities and the

potential increased collective risk that an action generates. Even with

disagreement on the level of the discount rate, a consensus favours

using declining risk-free discount rates over longer time horizons (high

confidence). [3.6.2]

An appropriate social risk-free discount rate for consumption

is between one and three times the anticipated growth rate in

real per capita consumption (medium confidence). This judgement

is based on an application of the Ramsey rule using typical values in

the literature of normative parameters in the rule. Ultimately, however,

these are normative choices. [3.6.2]

Co-benefits may complement the direct benefits of mitigation

(medium confidence). While some direct benefits of mitigation are

reductions in adverse climate change impacts, co-benefits can include

a broad range of environmental, economic, and social effects, such as

212212

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

reductions in local air pollution, less acid rain, and increased energy

security. However, whether co-benefits are net positive or negative in

terms of wellbeing (welfare) can be difficult to determine because of

interaction between climate policies and pre-existing non-climate poli-

cies. The same results apply to adverse side-effects. [3.6.3]

Tax distortions change the cost of all abatement policies (high

confidence). A carbon tax or a tradable emissions permit system can

exacerbate tax distortions, or, in some cases, alleviate them; carbon tax

or permit revenue can be used to moderate adverse effects by cutting

other taxes. However, regulations that forgo revenue (e. g., by giving

permits away) implicitly have higher social costs because of the tax

interaction effect. [3.6.3]

Many different analytic methods are available for evaluating

policies� Methods may be quantitative (for example, cost-benefit

analysis, integrated assessment modelling, and multi-criteria analysis)

or qualitative (for example, sociological and participatory approaches).

However, no single-best method can provide a comprehensive analysis

of policies. A mix of methods is often needed to understand the broad

effects, attributes, trade-offs, and complexities of policy choices; more-

over, policies often address multiple objectives. [3.7]

Four main criteria are frequently used in evaluating and choos-

ing a mitigation policy (medium confidence). They are: cost-effec-

tiveness and economic efficiency (excluding environmental benefits,

but including transaction costs); environmental effectiveness (the

extent to which the environmental targets are achieved); distributional

effects (impact on different subgroups within society); and institutional

feasibility, including political feasibility. [3.7.1]

A broad range of policy instruments for climate change miti-

gation is available to policymakers� These include: economic

incentives, direct regulatory approaches, information programmes,

government provision, and voluntary actions. Interactions between

policy instruments can enhance or reduce the effectiveness and cost

of mitigation action. Economic incentives will generally be more

cost-effective than direct regulatory interventions. However, the

performance and suitability of policies depends on numerous con-

ditions, including institutional capacity, the influence of rent-seek-

ing, and predictability or uncertainty about future policy settings.

The enabling environment may differ between countries, including

between low-income and high-income countries. These differences

can have implications for the suitability and performance of policy

instruments. [3.8]

Impacts of extreme events may be more important economi-

cally than impacts of average climate change (high confidence).

Risks associated with the entire probability distribution of outcomes

in terms of climate response [WGI] and climate impacts [WGII] are

relevant to the assessment of mitigation. Impacts from more extreme

climate change may be more important economically (in terms of the

expected value of impacts) than impacts of average climate change,

particularly if the damage from extreme climate change increases more

rapidly than the probability of such change declines. This is important

in economic analysis, where the expected benefit of mitigation may be

traded off against mitigation costs. [3.9.2]

Impacts from climate change are both market and non-market�

Market effects (where market prices and quantities are observed)

include impacts of storm damage on infrastructure, tourism, and

increased energy demand. Non-market effects include many ecological

impacts, as well as changed cultural values, none of which are gen-

erally captured through market prices. The economic measure of the

value of either kind of impact is ‘willingness-to-pay’ to avoid damage,

which can be estimated using methods of revealed preference and

stated preference. [3.9]

Substitutability reduces the size of damages from climate

change (high confidence). The monetary damage from a change in the

climate will be lower if individuals can easily substitute for what is

damaged, compared to cases where such substitution is more difficult.

[3.9]

Damage functions in existing Integrated Assessment Models

(IAMs) are of low reliability (high confidence). The economic assess-

ments of damages from climate change as embodied in the damage

functions used by some existing IAMs (though not in the analysis

embodied in WGIII) are highly stylized with a weak empirical foun-

dation. The empirical literature on monetized impacts is growing but

remains limited and often geographically narrow. This suggests that

such damage functions should be used with caution and that there

may be significant value in undertaking research to improve the preci-

sion of damage estimates. [3.9, 3.12]

Negative private costs of mitigation arise in some cases,

although they are sometimes overstated in the literature

(medium confidence). Sometimes mitigation can lower the private

costs of production and thus raise profits; for individuals, mitigation

can raise wellbeing. Ex-post evidence suggests that such ‘negative cost

opportunities’ do indeed exist but are sometimes overstated in engi-

neering analyses. [3.9]

Exchange rates between GHGs with different atmospheric life-

times are very sensitive to the choice of emission metric� The

choice of an emission metric depends on the potential application and

involves explicit or implicit value judgements; no consensus surrounds

the question of which metric is both conceptually best and practical to

implement (high confidence). In terms of aggregate mitigation costs

alone, the Global Warming Potential (GWP), with a 100-year time hori-

zon, may perform similarly to selected other metrics (such as the time-

dependent Global Temperature Change Potential or the Global Cost

Potential) of reaching a prescribed climate target; however, various

metrics may differ significantly in terms of the implied distribution of

costs across sectors, regions, and over time (limited evidence, medium

agreement). [3.9]

213213

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

The behaviour of energy users and producers exhibits a variety

of anomalies (high confidence). Understanding climate change as a

physical phenomenon with links to societal causes and impacts is a

very complex process. To be fully effective, the conceptual frameworks

and methodological tools used in mitigation assessments need to take

into account cognitive limitations and other-regarding preferences that

frame the processes of economic decision making by people and firms.

[3.10]

Perceived fairness can facilitate cooperation among individu-

als (high confidence). Experimental evidence suggests that reciprocal

behaviour and perceptions of fair outcomes and procedures facilitate

voluntary cooperation among individual people in providing public

goods; this finding may have implications for the design of interna-

tional agreements to coordinate climate change mitigation. [3.10]

Social institutions and culture can facilitate mitigation and

adaptation (medium confidence). Social institutions and culture can

shape individual actions on mitigation and adaptation and be comple-

mentary to more conventional methods for inducing mitigation and

adaptation. They can promote trust and reciprocity and contribute to

the evolution of common rules. They also provide structures for acting

collectively to deal with common challenges. [3.10]

Technological change that reduces mitigation costs can be

encouraged by institutions and economic incentives (high con-

fidence). As pollution is not fully priced by the market, private indi-

viduals and firms lack incentives to invest sufficiently in the develop-

ment and use of emissions-reducing technologies in the absence of

appropriate policy interventions. Moreover, imperfect appropriability of

the benefits of innovation further reduces incentives to develop new

technologies. [3.11]

3.1 Introduction

This framing chapter has two primary purposes: to provide a frame-

work for viewing and understanding the human (social) perspective on

climate change, focusing on ethics and economics; and to define and

discuss key concepts used in other chapters. It complements the two

other framing chapters: Chapter 2 on risk and uncertainty and Chapter

4 on sustainability. The audience for this chapter (indeed for this entire

volume) is decision makers at many different levels.

The significance of the social dimension and the role of ethics and eco-

nomics is underscored by Article 2 of the United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which indicates that the

ultimate objective of the Convention is to avoid dangerous anthropo-

genic interference with the climate system. Two main issues confront-

ing society are: what constitutes ‘dangerous interference’ with the

climate system and how to deal with that interference (see box 3.1).

Providing information to answer these inter-related questions is a pri-

mary purpose of the IPCC. Although natural science helps us under-

stand how emissions can change the climate, and, in turn, generate

physical impacts on ecosystems, people, and the physical environment,

determining what is dangerous involves judging the level of adverse

consequences, the steps necessary to mitigate these consequences,

and the risk that humanity is willing to tolerate. These are questions

requiring value judgement. Although economics is essential to evaluat-

ing the consequences and trade-offs associating with climate change,

how society interprets and values them is an ethical question.

Our discussion of ethics centres on two main considerations: justice

and value. Justice requires that people and nations should receive

what they are due, or have a right to. For some, an outcome is just

if the process that generated it is just. Others view justice in terms

of the actual outcomes enjoyed by different people and groups and

the values they place on those outcomes. Outcome-based justice can

range from maximizing economic measures of aggregate welfare to

rights-based views of justice, for example, believing that all countries

have a right to clean air. Different views have been expressed about

what is valuable. All values may be anthropocentric or there may be

non-human values. Economic analysis can help to guide policy action,

provided that appropriate, adequate, and transparent ethical assump-

tions are built into the economic methods.

The significance of economics in tackling climate change is widely rec-

ognized. For instance, central to the politics of taking action on climate

change are disagreements over how much mitigation the world should

undertake, and the economic costs of action (the costs of mitigation)

and inaction (the costs of adaptation and residual damage from a

changed climate). Uncertainty remains about (1) the costs of reducing

emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs), (2) the damage caused by a

change in the climate, and (3) the cost, practicality, and effectiveness

of adaptation measures (and, potentially, geoengineering). Prioritiz-

ing action on climate change over other significant social goals with

more near-term payoffs is particularly difficult in developing countries.

Because social concerns and objectives, such as the preservation of

traditional values, cannot always be easily quantified or monetized,

economic costs and benefits are not the only input into decision mak-

ing about climate change. But even where costs and benefits can be

quantified and monetized, using methods of economic analysis to

steer social action implicitly involves significant ethical assumptions.

This chapter explains the ethical assumptions that must be made for

economic methods, including cost-benefit analysis (CBA), to be valid,

as well as the ethical assumptions that are implicitly being made

where economic analysis is used to inform a policy choice.

The perspective of economics can improve our understanding of the

challenges of acting on mitigation. For an individual or firm, mitigation

involves real costs, while the benefits to themselves of their own miti-

gation efforts are small and intangible. This reduces the incentives for

individuals or countries to unilaterally reduce emissions; free-riding on

the actions of others is a dominant strategy. Mitigating greenhouse

214214

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

gas (GHG) emissions is a public good, which inhibits mitigation. This

also partly explains the failure of nations to agree on how to solve the

problem.

In contrast, adaptation tends not to suffer from free-riding. Gains to

climate change from adaptation, such as planting more heat tolerant

crops, are mainly realized by the parties who incur the costs. Associated

externalities tend to be more localized and contemporaneous than for

GHG mitigation. From a public goods perspective, global coordination

may be less important for many forms of adaptation than for mitiga-

tion. For autonomous adaptation in particular, the gains from adapta-

tion accrue to the party incurring the cost. However, public adaptation

requires local or regional coordination. Financial and other constraints

may restrict the pursuit of attractive adaptation opportunities, particu-

larly in developing countries and for poorer individuals.

This chapter addresses two questions: what should be done about

action to mitigate climate change (a normative issue) and how the

world works in the multifaceted context of climate change (a descrip-

tive or positive issue). Typically, ethics deals with normative questions

and economics with descriptive or normative questions. Descriptive

questions are primarily value-neutral, for example, how firms have

reacted to cap-and-trade programmes to limit emissions, or how soci-

eties have dealt with responsibility for actions that were not known to

be harmful when they were taken. Normative questions use economics

and ethics to decide what should be done, for example, determining

the appropriate level of burden sharing among countries for current

and future mitigation. In making decisions about issues with norma-

tive dimensions, it is important to understand the implicit assumptions

involved. Most normative analyses of solutions to the climate problem

implicitly involve contestable ethical assumptions.

This chapter does not attempt to answer ethical questions, but rather

provides policymakers with the tools (concepts, principles, arguments,

and methods) to make decisions. Summarizing the role of economics

and ethics in climate change in a single chapter necessitates several

caveats. While recognizing the importance of certain non-economic

social dimensions of the climate change problem and solutions to it,

space limitations and our mandate necessitated focusing primarily on

ethics and economics. Furthermore, many of the issues raised have

already been addressed in previous IPCC assessments, particularly AR2

(published in 1995). In the past, ethics has received less attention than

economics, although aspects of both subjects are covered in AR2. The

literature reviewed here includes pre-AR4 literature in order to pro-

vide a more comprehensive understanding of the concepts and meth-

ods. We highlight ‘new’ developments in the field since the last IPCC

assessment in 2007.

3.2 Ethical and socio-economic

concepts and principles

When a country emits GHGs, its emissions cause harm around the

globe. The country itself suffers only a part of the harm it causes. It is

therefore rarely in the interests of a single country to reduce its own

emissions, even though a reduction in global emissions could benefit

every country. That is to say, the problem of climate change is a “trag-

edy of the commons” (Hardin, 1968). Effective mitigation of climate

change will not be achieved if each person or country acts indepen-

dently in its own interest.

Consequently, efforts are continuing to reach effective international

agreement on mitigation. They raise an ethical question that is widely

recognized and much debated, namely, ‘burden-sharing’ or ‘effort-

sharing’. How should the burden of mitigating climate change be

divided among countries? It raises difficult issues of justice, fairness,

and rights, all of which lie within the sphere of ethics.

Burden-sharing is only one of the ethical questions that climate change

raises.

1

Another is the question of how much overall mitigation should

1

A survey of the ethics of climate change is Gardiner (2004), pp. 555 – 600.

Box 3�1 | Dangerous interference with the climate system

Article 2 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate

Change states that “the ultimate objective of the Convention

[…] is to achieve […] stabilization of greenhouse gas concentra-

tions in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous

anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” Judging

whether our interference in the climate system is dangerous, i. e.,

risks causing a very bad outcome, involves two tasks: estimat-

ing the physical consequences of our interference and their

likelihood; and assessing their significance for people. The first

falls to science, but, as the Synthesis Report of the IPCC Fourth

Assessment Report (AR4) states, “Determining what constitutes

‘dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’

in relation to Article 2 of the UNFCCC involves value judgements”

(IPCC, 2007, p.42). Value judgements are governed by the theory

of value. In particular, valuing risk is covered by decision theory

and is dealt with in Chapter 2. Central questions of value that

come within the scope of ethics, as well as economic methods for

measuring certain values are examined in this chapter.

215215

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

take place. UNFCCC sets the aim of “avoiding dangerous anthropo-

genic interference with the climate system”, and judging what is dan-

gerous is partly a task for ethics (see Box 3.1). Besides justice, fairness,

and rights, a central concern of ethics is value. Judgements of value

underlie the question of what interference with the climate system

would be dangerous.

Indeed, ethical judgements of value underlie almost every decision

that is connected with climate change, including decisions made by

individuals, public and private organizations, governments, and group-

ings of governments. Some of these decisions are deliberately aimed at

mitigating climate change or adapting to it. Many others influence the

progress of climate change or its impacts, so they need to take climate

change into account.

Ethics may be broadly divided into two branches: justice and value.

Justice is concerned with ensuring that people get what is due to them.

If justice requires that a person should not be treated in a particular

way — uprooted from her home by climate change, for example — then

the person has a right not to be treated that way. Justice and rights are

correlative concepts. On the other hand, criteria of value are concerned

with improving the world: making it a better place. Synonyms for

‘value’ in this context are ‘good’, ‘goodness’ and ‘benefit’. Antonyms

are ‘bad’, ‘harm’ and ‘cost’.

To see the difference between justice and value, think of a transfer of

wealth made by a rich country to a poor one. This may be an act of

restitution. For example, it may be intended to compensate the poor

country for harm that has been done to it by the rich country’s emis-

sions of GHG. In this case, the transfer is made on grounds of justice.

The payment is taken to be due to the poor country, and to satisfy a

right that the poor country has to compensation. Alternatively, the rich

country may make the transfer to support the poor country’s mitiga-

tion effort, because this is beneficial to people in the poor country,

the rich country, and elsewhere. The rich country may not believe the

poor country has a right to the support, but makes the payment simply

because it does ‘good’. This transfer is made on grounds of value. What

would be good to do is not necessarily required as a matter of justice.

Justice is concerned with what people are entitled to as a matter of

their rights.

The division between justice and value is contested within moral phi-

losophy, and so is the nature of the interaction between the two.

Some authors treat justice as inviolable (Nozick, 1974): justice sets

limits on what we may do and we may promote value only within

those limits. An opposite view — called ‘teleological’ by Rawls

(1971) — is that the right decision to make is always determined

by the value of the alternatives, so justice has no role. But despite

the complexity of their relationship and the controversies it raises,

the division between justice and value provides a useful basis for

organizing the discussion of ethical concepts and principles. We

have adopted it in this chapter: sections 3.3 and 3.4 cover justice

and value, respectively. One topic appears in both sections because

it bridges the divide: this topic is distributive justice viewed one way

and the value of equality viewed the other. Section 3.3.7 on geoen-

gineering is also in an intermediate position because it raises ethical

issues of both sorts. Section 3.6 explains how some ethical values

can be measured by economic methods of valuation. Section 3.5

describes the scope and limitations of these methods. Later sections

develop the concepts and methods of economics in more detail. Prac-

tical ways to take account of different values in policy-making are

discussed in Section 3.7.1.

3.3 Justice, equity and

responsibility

Justice, fairness, equity, and responsibility are important in interna-

tional climate negotiations, as well as in climate-related political deci-

sion making within countries and for individuals.

In this section we examine distributive justice, which, for the purpose

of this review, is about outcomes, and procedural justice or the way in

which outcomes are brought about. We also discuss compensation for

damage and historic responsibility for harm. In the context of climate

change, considerations of justice, equity, and responsibility concern the

relations between individuals, as well as groups of individuals (e. g.,

countries), both at a single point in time and across time. Accordingly,

we distinguish intra-generational from intergenerational justice. The

literature has no agreement on a correct answer to the question, what

is just? We indicate where opinions differ.

3�3�1 Causal and moral responsibility

From the perspective of countries rather than individuals or groups of

individuals, historic emissions can help determine causal responsibil-

ity for climate change (den Elzen etal., 2005; Lamarque etal., 2010;

Höhne etal., 2011). Many developed countries are expected to suf-

fer relatively modest physical damage and some are even expected to

realize benefits from future climate change (see Tol, 2002a; b). On the

other hand, some developing countries bear less causal responsibil-

ity, but could suffer significant physical damage from climate change

(IPCC, 2007, WG II AR4 SPM). This asymmetry gives rise to the follow-

ing questions of justice and moral responsibility: do considerations of

justice provide guidance in determining the appropriate level of pres-

ent and future global emissions; the distribution of emissions among

those presently living; and the role of historical emissions in distribut-

ing global obligations? The question also arises of who might be con-

sidered morally responsible for achieving justice, and, thus, a bearer of

duties towards others. The question of moral responsibility is also key

to determining whether anyone owes compensation for the damage

caused by emissions.

216216

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

3�3�2 Intergenerational justice and rights of

future people

Intergenerational justice encompasses some of the moral duties owed

by present to future people and the rights that future people hold

against present people.

2

A legitimate acknowledgment that future or

past generations have rights relative to present generations is indica-

tive of a broad understanding of justice.

3

While justice considerations

so understood are relevant, they cannot cover all our concerns regard-

ing future and past people, including the continued existence of

humankind and with a high level of wellbeing.

4

What duties do present generations owe future generations given that

current emissions will affect their quality of life? Some justice theo-

rists have offered the following argument to justify a cap on emissions

(Shue, 1993, 1999; Caney, 2006a; Meyer and Roser, 2009; Wolf, 2009).

If future people’s basic rights include the right to survival, health, and

subsistence, these basic rights are likely to be violated when tempera-

tures rise above a certain level. However, currently living people can

slow the rise in temperature by limiting their emissions at a reason-

able cost to themselves. Therefore, living people should reduce their

emissions in order to fulfil their minimal duties of justice to future

generations. Normative theorists dispute the standard of living that

corresponds to people’s basic rights (Page, 2007; Huseby, 2010). Also

in dispute is what level of harm imposed on future people is morally

objectionable. Some argue that currently living people wrongfully

harm future people if they cause them to have a lower level of well-

being than their own (e. g., Barry, 1999); others that currently living

people owe future people a decent level of wellbeing, which might be

lower than their own (Wolf, 2009). This argument raises objections on

grounds of justice since it presupposes that present people can violate

the rights of future people, and that the protection of future people’s

rights is practically relevant for how present people ought to act.

Some theorists claim that future people cannot hold rights against

present people, owing to special features of intergenerational rela-

tions: some claim that future people cannot have rights because they

cannot exercise them today (Steiner, 1983; Wellman, 1995, ch. 4). Oth-

ers point out that interaction between non-contemporaries is impos-

sible (Barry, 1977, pp. 243 – 244, 1989, p.189). However, some justice

theorists argue that neither the ability to, nor the possibility of, mutual

interaction are necessary in attributing rights to people (Barry, 1989;

Buchanan, 2004). They hold that rights are attributed to beings whose

interests are important enough to justify imposing duties on others.

2

In the philosophical literature, “justice between generations” typically refers to

the relations between people whose lifetimes do not overlap (Barry, 1977). In

contrast, “justice between age groups” refers to the relations of people whose

lifetimes do overlap (Laslett and Fishkin, 1992). See also Gardiner (2011),

pp.145 – 48.

3

See Rawls (1971, 1999), Barry (1977), Sikora and Barry (1978), Partridge (1981),

Parfit (1986), Birnbacher (1988), and Heyd (1992).

4

See Baier (1981), De-Shalit (1995), Meyer (2005), and for African philosophi-

cal perspectives see, Behrens (2012). See Section 3.4 on the wellbeing of future

people.

The main source of scepticism about the rights of future people and

the duties we owe them is the so-called ‘non-identity problem’. Actions

we take to reduce our emissions will change people’s way of life and

so affect new people born. They alter the identities of future people.

Consequently, our emissions do not make future people worse off than

they would otherwise have been, since those future people would not

exist if we took action to prevent our emissions. This makes it hard to

claim that our emissions harm future people, or that we owe it to them

as a matter of their rights to reduce our emissions.

5

It is often argued that the non-identity problem can be overcome

(McMahan, 1998; Shiffrin, 1999; Kumar, 2003; Meyer, 2003; Harman,

2004; Reiman, 2007; Shue, 2010). In any case, duties of justice do not

include all the moral concerns we should have for future people. Other

concerns are matters of value rather than justice, and they too can be

understood in such a way that they are not affected by the non-iden-

tity problem. They are considered in Section 3.4.

If present people have a duty to protect future people’s basic rights,

this duty is complicated by uncertainty. Present people’s actions or

omissions do not necessarily violate future people’s rights; they create

a risk of their rights being violated (Bell, 2011). To determine what cur-

rently living people owe future people, one has to weigh such uncer-

tain consequences against other consequences of their actions, includ-

ing the certain or likely violation of the rights of currently living people

(Oberdiek, 2012; Temkin, 2012). This is important in assessing many

long-term policies, including on geoengineering (see Section 3.3.7),

that risk violating the rights of many generations of people (Crutzen,

2006; Schneider, 2008; Victor etal., 2009; Baer, 2010; Ott, 2012).

3�3�3 Intergenerational justice: distributive

justice

Suppose that a global emissions ceiling that is intergenerationally just

has been determined (recognizing that a ceiling is not the only way to

deal with climate change), the question then arises of how the ceil-

ing ought to be divided among states (and, ultimately, their individ-

ual members) (Jamieson, 2001; Singer, 2002; Meyer and Roser, 2006;

Caney, 2006a). Distributing emission permits is a way of arriving at a

globally just division. Among the widely discussed views on distribu-

tive justice are strict egalitarianism (Temkin, 1993), indirect egalitarian

views including prioritarianism (Parfit, 1997), and sufficientarianism

(Frankfurt, 1999). Strict egalitarianism holds that equality has value

in itself. Prioritarianism gives greater weight to a person’s wellbeing

the less well off she is, as described in Section 3.4. Sufficientarianism

recommends that everyone should be able to enjoy a particular level

of wellbeing.

5

For an overview of the issue see Meyer (2010). See also Schwartz (1978), Parfit

(1986), and Heyd (1992). For a different perspective see Perrett (2003).

217217

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

For example, two options can help apply prioritarianism to the dis-

tribution of freely allocated and globally tradeable emission permits.

The first is to ignore the distribution of other goods. Then strict egali-

tarianism or prioritarianism will require emission permits to be distrib-

uted equally, since they will have one price and are thus equivalent

to income. The second is to take into account the unequal distribution

of other assets. Since people in the developing world are less well off

than in the developed world, strict egalitarianism or prioritarianism

would require most or all permits to go to the developing world. How-

ever, it is questionable whether it is appropriate to bring the overall

distribution of goods closer to the prioritarian ideal through the dis-

tribution of just one good (Wolff and de-Shalit, 2007; Caney, 2009,

2012).

3�3�4 Historical responsibility and distributive

justice

Historical responsibility for climate change depends on countries’ con-

tributions to the stock of GHGs. The UNFCCC refers to “common but

differentiated responsibilities” among countries of the world.

6

This is

sometimes taken to imply that current and historical causal responsi-

bility for climate change should play a role in determining the obliga-

tions of different countries in reducing emissions and paying for adap-

tation measures globally (Rajamani, 2000; Rive et al., 2006; Friman,

2007).

A number of objections have been raised against the view that his-

torical emissions should play a role (see, e. g., Gosseries, 2004; Caney,

2005; Meyer and Roser, 2006; Posner and Weisbach, 2010). First, as

currently living people had no influence over the actions of their ances-

tors, they cannot be held responsible for them. Second, previously liv-

ing people may be excused from responsibility on the grounds that

they could not be expected to know that their emissions would have

harmful consequences. Thirdly, present individuals with their particu-

lar identities are not worse or better off as a result of the emission-

generating activities of earlier generations because, owing to the non-

identity problem, they would not exist as the individuals they are had

earlier generations not acted as they did.

From the perspective of distributive justice, however, these objections

need not prevent past emissions and their consequences being taken

into account (Meyer and Roser, 2010; Meyer, 2013). If we are only

concerned with the distribution of benefits from emission-generating

activities during an individual’s lifespan, we should include the ben-

efits present people have received from their own emission-generating

activities. Furthermore, present people have benefited since birth or

conception from past people’s emission-producing actions. They are

6

Specifically, Article 3 of the UNFCCC includes the sentence: “The Parties should

protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of

humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but dif-

ferentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.”

therefore better off as a result of past emissions, and any principle of

distributive justice should take that into account. Some suggest that

taking account of the consequences of some past emissions in this

way should not be subject to the objections mentioned in the previous

paragraph (see Shue, 2010). Other concepts associated with historical

responsibility are discussed in Chapter 4.

3�3�5 Intra-generational justice: compensatory

justice and historical responsibility

Do those who suffer disproportionately from the consequences of cli-

mate change have just claims to compensation against the main per-

petrators or beneficiaries of climate change (see, e. g., Neumayer, 2000;

Gosseries, 2004; Caney, 2006b)?

One way of distinguishing compensatory from distributive claims is to

rely on the idea of a just baseline distribution that is determined by

a criterion of distributive justice. Under this approach, compensation

for climate damage and adaptation costs is owed only by people who

have acted wrongfully according to normative theory (Feinberg, 1984;

Coleman, 1992; McKinnon, 2011). Other deviations from the baseline

may warrant redistributive measures to redress undeserved benefits or

harms, but not as compensation. Some deviations, such as those that

result from free choice, may not call for any redistribution at all.

The duty to make compensatory payments (Gosseries, 2004; Caney,

2006b) may fall on those who emit or benefit from wrongful emis-

sions or who belong to a community that produced such emissions.

Accordingly, three principles of compensatory justice have been sug-

gested: the polluter pays principle (PPP), the beneficiary pays princi-

ple (BPP), and the community pays principle (CPP) (Meyer and Roser,

2010; Meyer, 2013). None of the three measures is generally accepted,

though the PPP is more widely accepted than the others. The PPP

requires the emitter to pay compensation if the agent emitted more

than its fair share (determined as outlined in Section 3.3.2) and it

either knew, or could reasonably be expected to know, that its emis-

sions were harmful. The victim should be able to show that the emis-

sions either made the victim worse off than before or pushed below a

specified threshold of harm, or both.

The right to compensatory payments for wrongful emissions under PPP

has at least three basic limitations. Two have already been mentioned

in Section 3.3.4. Emissions that took place while it was permissible

to be ignorant of climate change (when people neither did know nor

could be reasonably be expected to know about the harmful conse-

quences of emissions) may be excused (Gosseries, 2004, pp. 39 – 41).

See also Section 3.3.6. The non-identity problem (see Section 3.3.2)

implies that earlier emissions do not harm many of the people who

come into existence later. Potential duty bearers may be dead and can-

not therefore have a duty to supply compensatory measures. It may

therefore be difficult to use PPP in ascribing compensatory duties and

identifying wronged persons. The first and third limitations restrict the

218218

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

assignment of duties of compensation to currently living people for

their most recent emissions, even though many more people are caus-

ally responsible for the harmful effects of climate change. For future

emissions, the third limitation could be overcome through a climate

change compensation fund into which agents pay levies for imposing

the risk of harm on future people (McKinnon, 2011).

According to BPP, a person who is wrongfully better off relative to a

just baseline is required to compensate those who are worse off. Past

emissions benefit some and impose costs on others. If currently liv-

ing people accept the benefits of wrongful past emissions, it has been

argued that they take on some of the past wrongdoer’s duty of com-

pensation (Gosseries, 2004). Also, we have a duty to condemn injustice,

which may entail a duty not to benefit from an injustice that causes

harm to others (Butt, 2007). However, BPP is open to at least two

objections. First, duties of compensation arise only from past emissions

that have benefited present people; no compensation is owed for other

past emissions. Second, if voluntary acceptance of benefits is a con-

dition of their giving rise to compensatory duties, the bearers of the

duties must be able to forgo the benefits in question at a reasonable

cost.

Under CPP, moral duties can be attributed to people as members of

groups whose identity persists over generations (De-Shalit, 1995;

Thompson, 2009). The principle claims that members of a community,

including a country, can have collective responsibility for the wrongful

actions of other past and present members of the community, even

though they are not morally or causally responsible for those actions

(Thompson, 2001; Miller, 2004; Meyer, 2005). It is a matter of debate

under what conditions present people can be said to have inherited

compensatory duties. Although CPP purports to overcome the problem

that a polluter might be dead, it can justify compensatory measures

only for emissions that are made wrongfully. It does not cover emis-

sions caused by agents who were permissibly ignorant of their harm-

fulness. (The agent in this case may be the community or state).

The practical relevance of principles of compensatory justice is limited.

Insofar as the harms and benefits of climate change are undeserved,

distributive justice will require them to be evened out, independently

of compensatory justice. Duties of distributive justice do not presup-

pose any wrongdoing (see Section 3.3.4). For example, it has been

suggested on grounds of distributive justice that the duty to pay for

adaptation should be allocated on the basis of people’s ability to pay,

which partly reflects the benefit they have received from past emis-

sions (Jamieson, 1997; Shue, 1999; Caney, 2010; Gardiner, 2011).

However, present people and governments can be said to know about

both the seriously harmful consequences of their emission-generating

activities for future people and effective measures to prevent those

consequences. If so and if they can implement these measures at a rea-

sonable cost to themselves to protect future people’s basic rights (see,

e. g., Birnbacher, 2009; Gardiner, 2011), they might be viewed as owing

intergenerational duties of justice to future people (see Section 3.3.2).

3�3�6 Legal concepts of historical

responsibility

Legal systems have struggled to define the boundaries of responsibility

for harmful actions and are only now beginning to do so for climate

change. It remains unclear whether national courts will accept lawsuits

against GHG emitters, and legal scholars vigorously debate whether

liability exists under current law (Mank, 2007; Burns and Osofsky,

2009; Faure and Peeters, 2011; Haritz, 2011; Kosolapova, 2011; Kysar,

2011; Gerrard and Wannier, 2012). This section is concerned with moral

responsibility, which is not the same as legal responsibility. But moral

thinking can draw useful lessons from legal ideas.

Harmful conduct is generally a basis for liability only if it breaches

some legal norm (Tunc, 1983), such as negligence, or if it interferes

unreasonably with the rights of either the public or property owners

(Mank, 2007; Grossman, 2009; Kysar, 2011; Brunée etal., 2012; Gold-

berg and Lord, 2012; Koch etal., 2012). Liability for nuisance does not

exist if the agent did not know, or have reason to know, the effects

of its conduct (Antolini and Rechtschaffen, 2008). The law in connec-

tion with liability for environmental damage still has to be settled.

The European Union, but not the United States, recognizes exemption

from liability for lack of scientific knowledge (United States Congress,

1980; European Union, 2004). Under European law, and in some US

states, defendants are not responsible if a product defect had not yet

been discovered (European Commission, 1985; Dana, 2009). Some

legal scholars suggest that assigning blame for GHG emissions dates

back to 1990 when the harmfulness of such emissions was established

internationally, but others argue in favour of an earlier date (Faure and

Nollkaemper, 2007; Hunter and Salzman, 2007; Haritz, 2011). Legal

systems also require a causal link between a defendant’s conduct and

some identified harm to the plaintiff, in this case from climate change

(Tunc, 1983; Faure and Nollkaemper, 2007; Kosolapova, 2011; Kysar,

2011; Brunée etal., 2012; Ewing and Kysar, 2012; Goldberg and Lord,

2012). A causal link might be easier to establish between emissions

and adaptation costs (Farber, 2007). Legal systems generally also

require causal foreseeability or directness (Mank, 2007; Kosolapova,

2011; van Dijk, 2011; Ewing and Kysar, 2012), although some statutes

relax this requirement in specific cases (such as the US Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA),

commonly known as Superfund. Emitters might argue that their contri-

bution to GHG levels was too small and the harmful effects too indirect

and diffuse to satisfy the legal requirements (Sinnot-Armstrong, 2010;

Faure and Peeters, 2011; Hiller, 2011; Kysar, 2011; van Dijk, 2011; Ger-

rard and Wannier, 2012).

Climate change claims could also be classified as unjust enrichment

(Kull, 1995; Birks, 2005), but legal systems do not remedy all forms of

enrichment that might be regarded as ethically unjust (Zimmermann,

1995; American Law Institute, 2011; Laycock, 2012). Under some legal

systems, liability depends on whether benefits were conferred without

legal obligation or through a transaction with no clear change of own-

219219

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

ership (Zimmermann, 1995; American Law Institute, 2011; Laycock,

2012). It is not clear that these principles apply to climate change.

As indicated, legal systems do not recognize liability just because a

positive or negative externality exists. Their response depends on the

behaviour that caused the externality and the nature of the causal

link between the agent’s behaviour and the resulting gain or loss to

another.

3�3�7 Geoengineering, ethics, and justice

Geoengineering (also known as climate engineering [CE]), is large-

scale technical intervention in the climate system that aims to cancel

some of the effects of GHG emissions (for more details see Working

Group I (WGI) 6.5 and WGIII 6.9). Geoengineering represents a third

kind of response to climate change, besides mitigation and adaptation.

Various options for geoengineering have been proposed, including dif-

ferent types of solar radiation management (SRM) and carbon dioxide

removal (CDR). This section reviews the major moral arguments for and

against geoengineering technologies (for surveys see Robock, 2008;

Corner and Pidgeon, 2010; Gardiner, 2010; Ott, 2010; Betz and Cacean,

2012; Preston, 2013). These moral arguments do not apply equally to

all proposed geoengineering methods and have to be assessed on a

case-specific basis.

7

Three lines of argument support the view that geoengineering tech-

nologies might be desirable to deploy at some point in the future. First,

that humanity could end up in a situation where deploying geoengi-

neering, particularly SRM, appears as a lesser evil than unmitigated

climate change (Crutzen, 2006; Gardiner, 2010; Keith et al., 2010;

Svoboda, 2012a; Betz, 2012). Second, that geoengineering could be

a more cost-effective response to climate change than mitigation or

adaptation (Barrett, 2008). Such efficiency arguments have been criti-

cized in the ethical literature for neglecting issues such as side-effects,

uncertainties, or fairness (Gardiner, 2010, 2011; Buck, 2012). Third,

that some aggressive climate stabilization targets cannot be achieved

through mitigation measures alone and thus must be complemented

by either CDR or SRM (Greene etal., 2010; Sandler, 2012).

Geoengineering technologies face several distinct sets of objections.

Some authors have stressed the substantial uncertainties of large-

scale deployment (for overviews of geoengineering risks see also

7

While the literature typically associates some arguments with particular types of

methods (e. g., the termination problem with SRM), it is not clear that there are

two groups of moral arguments: those applicable to all SRM methods on the one

side and those applicable to all CDR methods on the other side. In other words,

the moral assessment hinges on aspects of geoengineering that are not connected

to the distinction between SRM and CDR.

Schneider (2008) and Sardemann and Grunwald (2010)), while others

have argued that some intended and unintended effects of both CDR

and SRM could be irreversible (Jamieson, 1996) and that some cur-

rent uncertainties are unresolvable (Bunzl, 2009). Furthermore, it has

been pointed out that geoengineering could make the situation worse

rather than better (Hegerl and Solomon, 2009; Fleming, 2010; Hamil-

ton, 2013) and that several technologies lack a viable exit option: SRM

in particular would have to be maintained as long as GHG concentra-

tions remain elevated (The Royal Society, 2009).

Arguments against geoengineering on the basis of fairness and jus-

tice deal with the intra-generational and intergenerational distribu-

tional effects. SRM schemes could aggravate some inequalities if, as

expected, they modify regional precipitation and temperature patterns

with unequal social impacts (Bunzl, 2008; The Royal Society, 2009;

Svoboda etal., 2011; Preston, 2012). Furthermore, some CDR methods

would require large-scale land transformations, potentially competing

with agricultural land-use, with uncertain distributive consequences.

Other arguments against geoengineering deal with issues including

the geopolitics of SRM, such as international conflicts that may arise

from the ability to control the “global thermostat” (e. g., Schelling,

1996; Hulme, 2009), ethics (Hale and Grundy, 2009; Preston, 2011;

Hale and Dilling, 2011; Svoboda, 2012b; Hale, 2012b), and a critical

assessment of technology and modern civilization in general (Fleming,

2010; Scott, 2012).

One of the most prominent arguments against geoengineering sug-

gests that geoengineering research activities might hamper mitigation

efforts (e. g., Jamieson, 1996; Keith, 2000; Gardiner, 2010), which pre-

sumes that geoengineering should not be considered an acceptable

substitute for mitigation. The central idea is that research increases the

prospect of geoengineering being regarded as a serious alternative to

emission reduction (for a discussion of different versions of this argu-

ment see Hale, 2012a; Hourdequin, 2012). Other authors have argued,

based on historical evidence and analogies to other technologies, that

geoengineering research might make deployment inevitable (Jamie-

son, 1996; Bunzl, 2009), or that large-scale field tests could amount to

full-fledged deployment (Robock etal., 2010). It has also been argued

that geoengineering would constitute an unjust imposition of risks

on future generations, because the underlying problem would not be

solved but only counteracted with risky technologies (Gardiner, 2010;

Ott, 2012; Smith, 2012). The latter argument is particularly relevant to

SRM technologies that would not affect greenhouse gas concentra-

tions, but it would also apply to some CDR methods, as there may be

issues of long-term safety and capacity of storage.

Arguments in favour of research on geoengineering point out that

research does not necessarily prepare for future deployment, but can,

on the contrary, uncover major flaws in proposed schemes, avoid pre-

mature CE deployment, and eventually foster mitigation efforts (e. g.

Keith etal., 2010). Another justification for Research and Development

(R&D) is that it is required to help decision-makers take informed deci-

sions (Leisner and Müller-Klieser, 2010).

220220

Social, Economic, and Ethical Concepts and Methods

3

Chapter 3

3.4 Values and wellbeing

One branch of ethics is the theory of value. Many different sorts of

value can arise, and climate change impinges on many of them. Value

affects nature and many aspects of human life. This section surveys

some of the values at stake in climate change, and examines how far

these values can be measured, combined, or weighed against each

other. Each value is subject to debate and disagreement. For example,

it is debatable whether nature has value in its own right, apart from

the benefit it brings to human beings. Decision-making about climate

change is therefore likely to be contentious.

Since values constitute only one part of ethics, if an action will increase

value overall it by no means follows that it should be done. Many