793

13

Livelihoods and Poverty

Coordinating Lead Authors:

Lennart Olsson (Sweden), Maggie Opondo (Kenya), Petra Tschakert (USA)

Lead Authors:

Arun Agrawal (USA), Siri H. Eriksen (Norway), Shiming Ma (China), Leisa N. Perch (Barbados),

Sumaya A. Zakieldeen (Sudan)

Contributing Authors:

Catherine Jampel (USA), Eric Kissel (USA), Valentina Mara (Romania), Andrei Marin (Norway),

David Satterthwaite (UK), Asuncion Lera St. Clair (Norway), Andy Sumner (UK)

Review Editors:

Susan Cutter (USA), Etienne Piguet (Switzerland)

Volunteer Chapter Scientist:

Anna Kaijser (Sweden)

This chapter should be cited as:

Olsson

, L., M. Opondo, P. Tschakert, A. Agrawal, S.H. Eriksen, S. Ma, L.N. Perch, and S.A. Zakieldeen, 2014:

Livelihoods and poverty. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and

Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir,

M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken,

P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and

New York, NY, USA, pp. 793-832.

13

794

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................... 796

13.1. Scope, Delineations, and Definitions: Livelihoods, Poverty, and Inequality ........................................................... 798

13.1.1. Livelihoods ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 798

13.1.1.1. Dynamic Livelihoods and Trajectories ................................................................................................................................ 798

13.1.1.2. Multiple Stressors .............................................................................................................................................................. 798

13.1.2. Dimensions of Poverty ...................................................................................................................................................................... 799

13.1.2.1. Framing and Measuring Multidimensional Poverty ........................................................................................................... 800

13.1.2.2. Geographic Distribution and Trends of the World’s Poor ................................................................................................... 801

13.1.2.3. Spatial and Temporal Scales of Poverty ............................................................................................................................. 801

13.1.3. Inequality and Marginalization ......................................................................................................................................................... 802

13.1.4. Interactions between Livelihoods, Poverty, Inequality, and Climate Change ..................................................................................... 802

13.2. Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Livelihoods and Poverty .................................................................... 803

13.2.1. Evidence of Observed Climate Change Impacts on Livelihoods and Poverty .................................................................................... 803

13.2.1.1. Impacts on Livelihood Assets and Human Capabilities ...................................................................................................... 803

13.2.1.2. Impacts on Livelihood Dynamics and Trajectories .............................................................................................................. 805

13.2.1.3. Impacts on Poverty Dynamics: Transient and Chronic Poverty ........................................................................................... 805

13.2.1.4. Poverty Traps and Critical Thresholds ................................................................................................................................. 806

13.2.1.5. Multidimensional Inequality and Vulnerability .................................................................................................................. 807

Box 13-1. Climate and Gender Inequality: Complex and Intersecting Power Relations .................................................. 808

13.2.2. Understanding Future Impacts of and Risks from Climate Change on Livelihoods and Poverty ........................................................ 810

13.2.2.1. Projected Risks and Impacts by Geographic Region .......................................................................................................... 810

13.2.2.2. Anticipated Impacts on Economic Growth and Agricultural Productivity ........................................................................... 810

13.2.2.3. Implications for Livelihood Assets, Trajectories, and Poverty Dynamics .............................................................................. 812

13.2.2.4. Impacts on Transient and Chronic Poverty, Poverty Traps, and Thresholds ......................................................................... 812

13.3. Assessment of Impacts of Climate Change Responses on Livelihoods and Poverty .............................................. 813

13.3.1. Impacts of Mitigation Responses ...................................................................................................................................................... 813

13.3.1.1. The Clean Development Mechanism ................................................................................................................................. 813

13.3.1.2. Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation ................................................................................. 814

13.3.1.3. Voluntary Carbon Offsets .................................................................................................................................................. 814

13.3.1.4. Biofuel Production and Large-Scale Land Acquisitions ...................................................................................................... 814

13.3.2. Impacts of Adaptation Responses on Poverty and Livelihoods ......................................................................................................... 815

13.3.2.1. Impacts of Adaptation Responses on Livelihoods and Poverty .......................................................................................... 815

13.3.2.2. Insurance Mechanisms for Adaptation .............................................................................................................................. 816

Table of Contents

795

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

13.4. Implications of Climate Change for Poverty Alleviation Efforts ............................................................................. 816

13.4.1. Lessons from Climate-Development Efforts ...................................................................................................................................... 816

Box 13-2. Lessons from Social Protection, Disaster Risk Reduction, and Energy Access ............................................................ 817

13.4.2. Toward Climate-Resilient Development Pathways ............................................................................................................................ 818

13.5. Synthesis and Research Gaps ................................................................................................................................. 818

References ......................................................................................................................................................................... 819

Frequently Asked Questions

13.1: What are multiple stressors and how do they intersect with inequalities to influence livelihood trajectories? ................................ 799

13.2: How important are climate change-driven impacts on poverty compared to other drivers of poverty? ............................................ 802

13.3: Are there unintended negative consequences of climate change policies for people who are poor? ............................................... 813

796

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

Executive Summary

This chapter discusses how livelihoods, poverty and the lives of poor people, and inequality interact with climate change, climate variability,

and extreme events in multifaceted and cross-scalar ways. It examines how current impacts of climate change, projected impacts up until

2100, and responses to climate change affect livelihoods and poverty. The Fourth Assessment Report stated that socially and economically

disadvantaged and marginalized people are disproportionally affected by climate change. However, no comprehensive review of climate

change, poverty, and livelihoods has been undertaken to date by the IPCC. This chapter addresses this gap, presenting evidence of the dynamic

interactions between these three principal factors. At the same time, the chapter recognizes that climate change is rarely the only factor that

affects livelihood trajectories and poverty dynamics; climate change interacts with a multitude of non-climatic factors, which makes detection

and attribution challenging.

Climate-related hazards exacerbate other stressors, often with negative outcomes for livelihoods, especially for people living in

poverty (high confidence).

• Climate-related hazards, including subtle shifts and trends to extreme events, affect poor people’s lives directly through impacts on

livelihoods, such as losses in crop yields, destroyed homes, food insecurity, and loss of sense of place, and indirectly through increased food

prices (robust evidence, high agreement). {13.2.1, 13.3}

• Changing climate trends lead to shifts in rural livelihoods with mixed outcomes, such as from crop-based to hybrid livestock-based

livelihoods or to wage labor in urban employment. Climate change is one stressor that shapes dynamic and differential livelihood

trajectories (robust evidence, high agreement). {13.1.4, 13.2.1.2}

• Urban and rural transient poor who face multiple deprivations slide into chronic poverty as a result of extreme events, or a series of events,

when unable to rebuild their eroded assets. Poverty traps also arise from food price increase, restricted mobility, and discrimination (limited

evidence, high agreement). {13.2.1.3-4}

• Many events that affect poor people are weather-related and remain unrecognized by standard climate observations in many low-income

countries, owing to short time series and geographically sparse, aggregated, or partial data, inhibiting detection and attribution. Such

events include short periods of extreme temperature, minor changes in the distribution of rainfall, and strong wind events (robust evidence,

high agreement). {13.2.1}

Observed evidence suggests that climate change and climate variability worsen existing poverty, exacerbate inequalities, and

trigger both new vulnerabilities and some opportunities for individuals and communities. Poor people are poor for different

reasons and thus are not all equally affected, and not all vulnerable people are poor. Climate change interacts with non-climatic

stressors and entrenched structural inequalities to shape vulnerabilities (very high confidence, based on robust evidence, high

agreement).

• Socially and geographically disadvantaged people exposed to persistent inequalities at the intersection of various dimensions of

discrimination based on gender, age, race, class, caste, indigeneity, and (dis)ability are particularly negatively affected by climate change

and climate-related hazards. Context-specific conditions of marginalization shape multidimensional vulnerability and differential impacts.

{13.1.2.3, 13.1.3., 13.2.1.5}

• Existing gender inequalities are increased or heightened by climate-related hazards. Gendered impacts result from customary and new

roles in society, often entailing higher workloads, occupational hazards indoors and outdoors, psychological and emotional distress, and

mortality in climate-related disasters. {13.2.1.5}

• There is little evidence that shows positive impacts of climate change on poor people, except isolated cases of social asset accumulation,

agricultural diversification, disaster preparedness, and collective action. The more affluent often take advantage of shocks and crises, given

their flexible assets and power status. {13.1.4, 13.2.1.4; Figure 13-3}

Climate change will create new poor between now and 2100, in developing and developed countries, and jeopardize sustainable

development. The majority of severe impacts are projected for urban areas and some rural regions in sub-Saharan Africa and

Southeast Asia (medium confidence, based on medium evidence, medium agreement).

• Future impacts of climate change, extending from the near term to the long term, mostly expecting 2°C scenarios, will slow down

economic growth and poverty reduction, further erode food security, and trigger new poverty traps, the latter particularly in urban areas

and emerging hotspots of hunger. {13.2.2.2, 13.2.2.4, 13.4}

797

13

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

• Climate change will exacerbate multidimensional poverty in most developing countries, including high mountain states, countries at risk

from sea level rise, and countries with indigenous peoples. Climate change will also create new poverty pockets in countries with increasing

inequality, in both developed and developing countries. {13.2.2}

• Wage-labor dependent poor households that are net buyers of food will be particularly affected due to food price increases, in urban and

rural areas, especially in regions with high food insecurity and high inequality (particularly in Africa), although the agricultural self-employed

could benefit {13.2.2.3-4}

Current policy responses for climate change mitigation or adaptation will result in mixed, and in some cases even detrimental,

outcomes for poor and marginalized people, despite numerous potential synergies between climate policies and poverty reduction

(medium confidence, based on limited evidence, high agreement).

• Mitigation policies with social co-benefits expected in their design, such as Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Reduction of

Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), have had limited or no effect in terms of poverty alleviation and

sustainable development. {13.3.1.1-2}

• Mitigation efforts focused on land acquisition for biofuel production show preliminary negative impacts on the lives of poor people, such

as dispossession of farmland and forests, in many developing countries, particularly for indigenous peoples and (women) smallholders.

{13.3.1.4}

• Insurance schemes, social protection programs, and disaster risk reduction may enhance long-term livelihood resilience among poor and

marginalized people, if policies address multidimensional poverty. {13.3.2.2, 13.4.1}

• Climate-resilient development pathways will have only marginal effects on poverty reduction, unless structural inequalities are addressed

and needs for equity among poor and non-poor people are met. {13.4.2}

798

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

13.1. Scope, Delineations, and Definitions:

Livelihoods, Poverty, and Inequality

Understanding the impacts of climate change on livelihoods and

p

overty requires examining the complexities of poverty and the lives of

poor and non-poor people, as well as the multifaceted and cross-scalar

intersections of poverty and livelihoods with climate change. This chapter

is devoted to exploring poverty in relation to climate change, a novelty

in the IPCC. It uses a livelihood lens to assess the interactions between

climate change and multiple dimensions of poverty. We use the term

“the poor,” not to homogenize, but to describe people living in poverty,

people facing multiple deprivations, and the socially and economically

disadvantaged, as part of a conceptualization broader than income-

based measures of poverty, acknowledging gradients of prosperity and

poverty. This livelihood lens also reveals how inequalities perpetuate

poverty to shape differential vulnerabilities and in turn the differentiated

impacts of climate change on individuals and societies. The chapter first

presents the concepts of livelihoods, poverty, and inequality, and their

relationships to each other and to climate change. Second, it describes

observed impacts of weather events and climate on livelihoods and

rural and urban poor people as well as projected impacts up to 2100.

We use “weather events and climate” as an umbrella term for climate

change, climate variability, and extreme events, and also highlight subtle

shifts in precipitation and localized weather events. Third, this chapter

discusses impacts of climate change mitigation and adaptation responses

on livelihoods and poverty. Finally, it outlines implications for poverty

alleviation efforts and climate-resilient development pathways.

Livelihoods and Poverty is a new chapter in the AR5. Although the WGII

AR4 contributions mentioned poverty, as one of several non-climatic

factors contributing to vulnerability, as a serious obstacle to effective

adaptation, and in the context of endemic poverty in Africa (Chapters

7, 8, 18, 20), no systematic assessment was undertaken. Livelihoods were

more frequently addressed in the AR4 and in the Special Report on

Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate

Change Adaptation (SREX), predominantly with reference to livelihood

strategies and opportunities, diversification, resource-dependent

communities, and sustainability. Yet, a comprehensive livelihood lens

for assessing impacts was lacking. This chapter addresses these gaps.

It assesses how climate change intersects with other stressors to shape

livelihood choices and trajectories, to affect the spatial and temporal

dimensions of poverty dynamics, and to reduce or exacerbate inequalities

given differential vulnerabilities.

13.1.1. Livelihoods

Livelihoods (see also Glossary) are understood as the ensemble or

opportunity set of capabilities, assets, and activities that are required

to make a living (Chambers and Conway, 1992; Ellis et al., 2003). They

depend on access to natural, human, physical, financial, social, and

cultural capital (assets); the social relations people draw on to combine,

transform, and expand their assets; and the ways people deploy and

enhance their capabilities to act and make lives meaningful (Scoones,

1998; Bebbington, 1999). Livelihoods are dynamic and people adapt and

change their livelihoods with internal and external stressors. Ultimately,

successful livelihoods transform assets into income, dignity, and agency,

t

o improve living conditions, a prerequisite for poverty alleviation (Sen,

1981).

Livelihoods are universal. Poor and rich people both pursue livelihoods

to make a living. However, as shown in this chapter, the adverse impacts

of weather events and climate increasingly threaten and erode basic needs,

capabilities, and rights, particularly among poor and disenfranchised

people, in turn reshaping their livelihoods (UNDP, 2007; Leary et al.,

2008; Adger, 2010; Quinn et al., 2011). Some livelihoods are directly

climate sensitive, such as rainfed smallholder agriculture, seasonal

employment in agriculture (e.g., tea, coffee, sugar), fishing, pastoralism,

and tourism. Climate change also affects households dependent on

informal livelihoods or wage labor in poor urban settlements, directly

through unsafe settlement structures or indirectly through rises in food

prices or migration.

13.1.1.1. Dynamic Livelihoods and Trajectories

A livelihood lens is a grounded and multidimensional perspective that

recognizes the flexibility and constraints with which people construct

their complex lives and adapt their livelihoods in dynamic ways. By

paying attention to the wider institutional, cultural, and policy contexts

as well as shocks, seasonality, and trends, this lens reveals processes

that push people onto undesirable trajectories or toward enhanced well-

being. Better infrastructure and technology as well as diversification of

assets, activities, and social support capabilities can boost livelihoods,

spreading risks and broadening opportunities (Batterbury, 2001; Ellis

et al., 2003; Clot and Carter, 2009; Carr, 2013; Reed et al., 2013). The

sustainable livelihoods framework (Chambers and Conway, 1992) is

widely used for identifying how specific strategies may lead to cycles

of livelihood improvements or critical thresholds beyond which certain

livelihoods are no longer sustainable (Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2008). It

emerged as a reaction to the predominantly structural views of poverty

and “underdevelopment” in the 1970s and became adopted by many

researchers and development agencies (Ellis and Biggs, 2001). With

the neoliberal turn in the late 1980s, the livelihoods approach became

associated with a more individualistic development agenda, stressing

various forms of capital (Scoones, 2009). Consequently, it has been

criticized for its analytical limitations, such as measuring capitals or

assets, especially social capital, and for not sufficiently explaining wider

structural processes (e.g., policies) and ecological impacts of livelihood

decisions (Small, 2007; Scoones, 2009). An overemphasis on capitals

also eclipses power dynamics and the position of households in class,

race, and other dimensions of inequality (Van Dijk, 2011).

13.1.1.2. Multiple Stressors

Livelihoods rarely face only one stressor or shock at a time. The literature

emphasizes the synergistic relationship between weather events and

climate and a variety of other environmental, social, economic, and

political stressors; together, they impinge on livelihoods and reinforce

each other in the process, often negatively (Reid and Vogel, 2006;

Schipper and Pelling, 2006; Easterling et al., 2007; IPCC, 2007; Morton,

2007; Tschakert, 2007; O’Brien et al., 2008; Eriksen and Silva, 2009;

Eakin and Wehbe, 2009; Ziervogel et al., 2010). “Double losers” may

799

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

emerge from simultaneous exposure to climatic change and other

stressors such as the spread of infectious diseases, rapid urbanization,

and economic globalization, where climate change acts as a threat

multiplier, further marginalizing vulnerable groups (O’Brien and Leichenko,

2000; Eriksen and Silva, 2009). Climatic and other stressors affect

livelihoods at different scales: spatial (e.g., village, nation) or temporal

(e.g., annual, multi-annual). Both direct and indirect impacts are often

amplified or weakened at different levels. Global or regional processes

generate a variety of stressors, typically mediated by cross-level

institutions, that result in locally experienced shocks (Reid and Vogel,

2006; Thomas et al., 2007; Paavola, 2008; Pouliotte et al., 2009; see also

Figure 13-1 in FAQ 13.1).

Multiple stressors, simultaneous and in sequence, shape livelihood

dynamics in distinct ways due to inequalities and differential vulnerabilities

between and within households. More affluent households may be able

to capitalize on shocks and crises while poorer households with fewer

options are forced to erode their assets. Limited ability to adapt and

some coping strategies may result in adverse consequences. Such

maladaptive actions (see Glossary, and Chapters 14, 16) undermine the

long-term sustainability of livelihoods, resulting in downward trajectories,

poverty traps, and exacerbated inequalities (Ziervogel et al., 2006;

Tanner and Mitchell, 2008; Barnett and O’Neill, 2010).

13.1.2. Dimensions of Poverty

Poverty is a complex concept with conflicting definitions and considerable

disagreement in terms of framings, methodologies, and measurements.

Despite different approaches emphasizing distinct aspects of poverty

at the individual or collective level—such as income, capabilities, and

quality of life (Laderchi et al., 2003)—poverty is recognized as

multidimensional (UNDP, 1990). It is influenced by social, economic,

institutional, political, and cultural drivers; its reversal requires efforts

Frequently Asked Questions

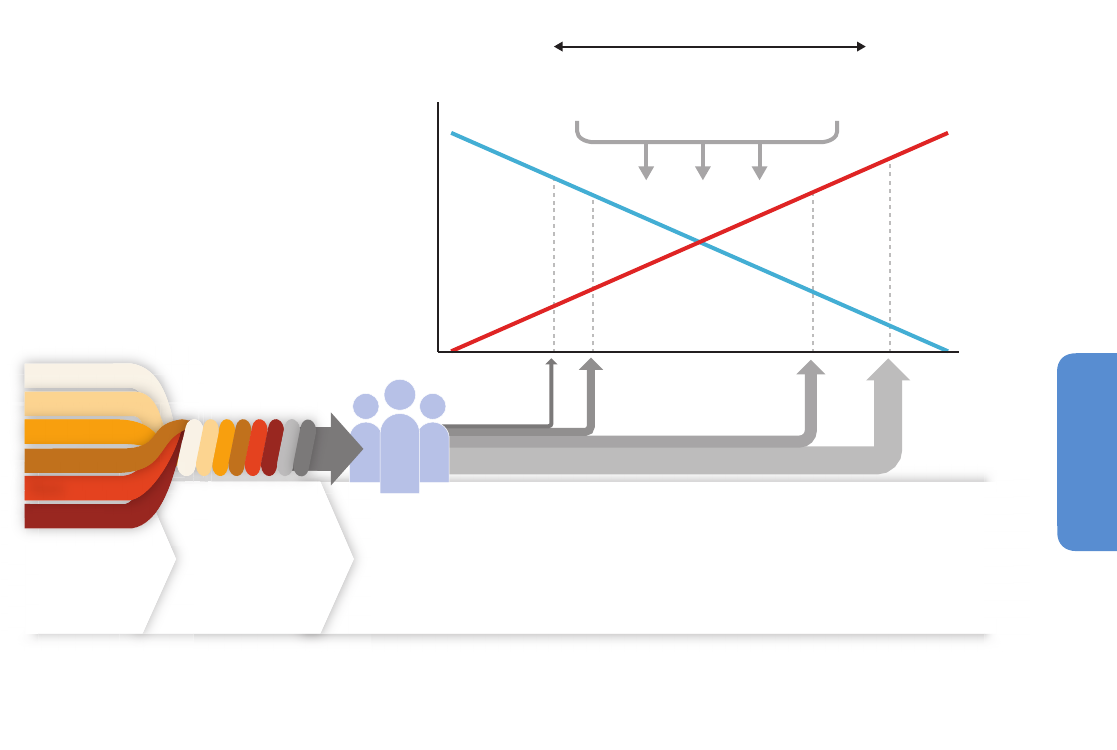

FAQ 13.1 | What are multiple stressors and how do they intersect with inequalities

to influence livelihood trajectories?

Multiple stressors are simultaneous or subsequent

conditions or events that provoke/require changes

in livelihoods. Stressors include climatic (e.g., shifts

in seasons), socioeconomic (e.g., market volatility),

and environmental (e.g., destruction of forest) factors,

that interact and reinforce each other across space

and time to affect livelihood opportunities and

decision making (see Figure 13-1). Stressors that

originate at the macro level include climate change,

globalization, and technological change. At the

regional, national, and local levels, institutional

context and policies shape possibilities and pitfalls

for lessening the effects of these stressors. Which

specific stressors ultimately result in shocks for

particular livelihoods and households is often

mediated by institutions that connect the local level

to higher levels. Moreover, inequalities in low-,

medium-, and high-income countries often amplify

the effects of these stressors. This is particularly the

case for livelihoods and households that have

limited asset flexibility and/or those that experience

disadvantages and marginalization due to gender,

age, class, race, (dis)ability, or being part of a particular

indigenous or ethnic group. Weather events and

climate compound these stressors, allowing some to benefit and enhance their well-being while others experience

severe shocks and may slide into chronic poverty. Who is affected, how, where, and for how long depends on local

contexts. For example, in the Humla district in Nepal, gender roles and caste relations influence livelihood trajectories

in the face of multiple stressors including shifts in the monsoon season (climatic), limited road linkages (socioeconomic),

and high elevation (environmental). Women from low castes have adapted their livelihoods by seeking more day-

labor employment, whereas men from low castes ventured into trading on the Nepal-China border, previously an

exclusively upper caste livelihood.

Livelihoods

Institutions such as:

•

Social protection

• Relief organizations

• Disaster prevention

Displacement

Destroyed

homes

Food

crisis

Figure 13-1 | Multiple stressors related to climate change, globalizations, and

technological change interact with national and regional institutions to create shocks

to place-based livelihoods, inspired by Reason (2000).

Climate change

Globalizations

Technological change

800

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

i

n multiple domains that promote opportunities and empowerment, and

enhance security (World Bank, 2001). In addition to material deprivation,

multidimensional conceptions of poverty consider a sense of belonging

and socio-cultural heritage (O’Brien and Leichenko, 2003), identity, and

agency, or “the culturally constrained capacity to act” (Ahearn, 2001,

p. 54). The AR4 identified poverty as “the most serious obstacle to

effective adaptation” (Confalonieri et al., 2007, p. 417).

13.1.2.1. Framing and Measuring Multidimensional Poverty

Over the last 6 decades, conceptualizations of poverty have broadened,

expanding the basis for understanding poverty and its drivers. Poverty

measurements now better capture multidimensional characteristics

and spatial and temporal nuances. Attention to multidimensional

deprivations—such as hunger; illiteracy; unclean drinking water; lack

of access to health, credit, or legal services; social exclusion; and

disempowerment—have shifted the analytical lens to the dynamics of

poverty and its institutionalization within social and political norms

(UNDP, 1994; Sen, 1999; World Bank, 2001). Regardless of these shifting

conceptualizations over time, comparable and reliable measures remain

challenging and income per capita remains the default method to

account for the depth of global poverty.

In climate change literature, poverty and poverty reduction have been

predominantly defined through an economic lens, reflecting various

growth and development discourses (Sachs, 2006; Collier, 2007). Less

a

ttention has been paid to relational poverty, produced through

material social relations and in relation to privilege and wealth (Sen,

1976; Mosse, 2010; Alkire and Foster, 2011; UNDP, 2011a). Yet, such

framing allows for addressing the social and political contexts that

generate and perpetuate poverty and structural vulnerability to climate

change (McCright and Dunlap, 2000; Bandiera et al., 2005; Leichenko

and O’Brien, 2008). Many climate policies to date favor market-based

responses using sector-specific and economic growth models of

development, although some responses may slow down achievements

of international development such as those outlined in the Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs). For instance, the World Bank encourages

“mitigation, adaptation, and the deployment of technologies” that

“allow[s] developing countries to continue their growth and reduce

poverty” (World Bank, 2010, p. 257), mainly promoted through market

tools. A relational approach to poverty highlights the integral role of

poor people in all social relations (Pogge, 2009; O’Brien et al., 2010;

UNRISD, 2010; Gasper et al., 2013; St.Clair and Lawson, 2013). It

emphasizes equity, human security, and dignity (O’Connor, 2002; Mosse,

2010). Akin to the capabilities approach (Sen, 1985, 1999; Nussbaum,

2001, 2011; Alkire, 2005), the relational approach stresses the needs,

skills, and aims of poor people while tackling structural causes of

poverty, inequalities, and uneven power relations.

The IPCC AR4 (Yohe et al., 2007) highlighted that—with very high

confidence—climate change will impede the ability of nations to

alleviate poverty and achieve sustainable development, as measured

by progress toward the MDGs. Empirical assessments of the impact of

0.00 – 0.06

0.06 – 0.11

0.11 – 0.18

0.18 – 0.30

0.30 – 0.47

no data

0.01 – 0.20

0.20 – 0.26

0.26 – 0.31

0.31 – 0.35

0.35 – 0.68

no data

10080604020

0

100

80

60

40

20

Philippines

Nicaragua

Gabon

Colombia

Thailand

Vietnam

Vietnam

Cameroon

Kenya

India

Gambia

Senegal

Uganda

Benin

Guinea

Niger

Central African

Republic

Rwanda

Malawi

Malawi

Madagascar

Poverty Gap Index

Poverty Gap Index

Uzbekistan

Laos

Haiti

Population below the international poverty line $1.25 per day (%)

Population in multidimensional poverty (%)

(a) (b)

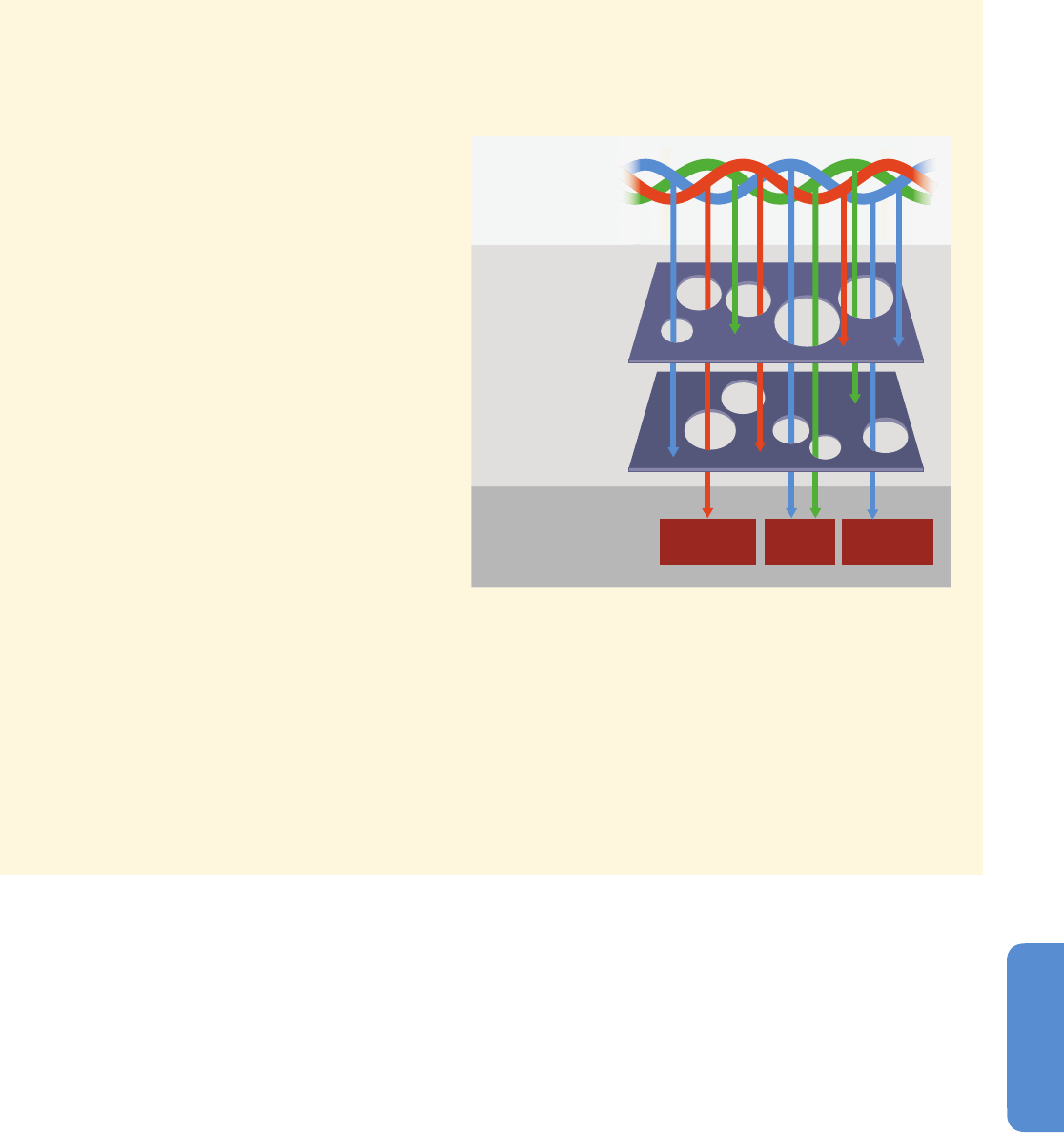

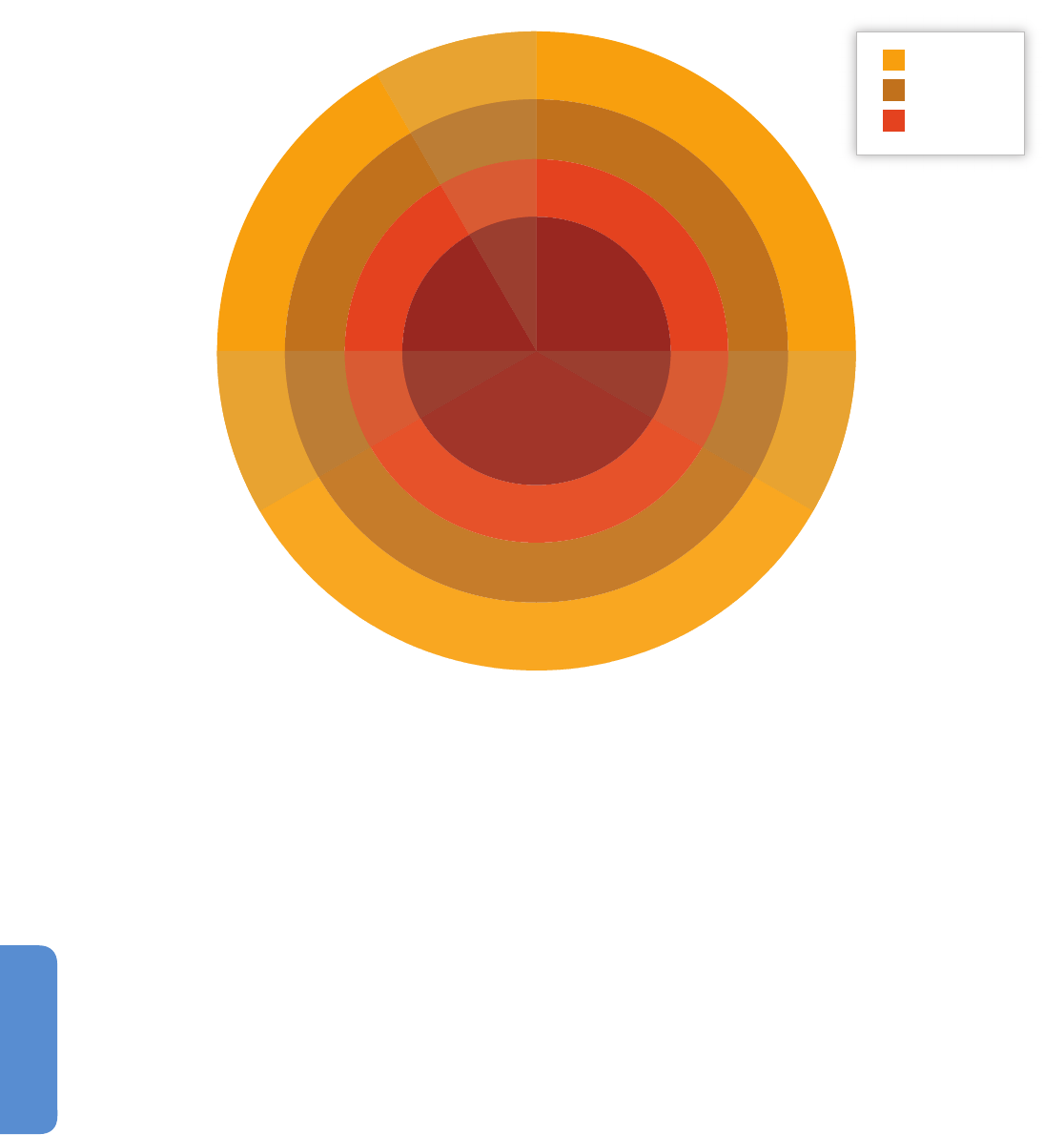

Figure 13-2 | (a) Multidimensional poverty and income-based poverty using the International Poverty Line $1.25 per day (in Purchasing Power Parity terms), with linear regression relationship

(dotted line) based on 96 countries (UNDP, 2011b). The position of the countries relative to the dotted line illustrates the extent to which these two poverty measures are similar or divergent.

(b) The map insets show the intensity of poverty in two countries, based on the Poverty Gap Index at district level (per capita measure of the shortfall in welfare of the poor from the poverty

line, expressed as a ratio of the poverty line): the darker the shading, the larger the shortfall.

801

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

c

limate change on MDG attainment are limited (Fankhauser and

Schmidt-Traub, 2011), and the failure to reach these goals by 2015 has

significant non-climatic causes (e.g., Hellmuth et al., 2007; UNDP, 2007).

The 2010 UNDP Multidimensional Poverty Index, measuring intensity of

poverty based on patterns of simultaneous deprivations in basic services

(education, health, and standard of living) and core human functionings,

states that close to 1.7 billion people face multidimensional poverty, a

significantly higher number than the 1.2 billion (World Bank, 2012a)

indicated by the International Poverty Line (IPL) set at $1.25 per day.

Figure 13-2 depicts country-level examples of how the two poverty

measures differ.

Caution is required for poverty projections. Estimates of poverty made

using national accounts means (see Chapter 19) yield drastically

different estimates to those produced by survey means, both for

current estimates and future projections (Edward and Sumner, 2013a).

Diverse conceptions of poverty further complicate projections, as

multidimensional conceptions rely on concepts difficult to measure

and compare. Data availability constrains current estimates let alone

projections and their core assumptions (Alkire and Santos, 2010; Karver

et al., 2012).

13.1.2.2. Geographic Distribution and Trends of the World’s Poor

Geographic patterns of poverty are uneven and shifting. Despite its

limitations, most comparisons to date rely on the IPL. In the remainder

of the text, we use the World Bank income-based poverty categories

for countries (low-income countries, lower-middle-income countries,

upper-middle-income countries, and high-income countries); these

categories are more precise and more accurate for describing climate

change impacts on poverty than the terminology adopted in the

Summary for Policymakers and the respective chapter Executive

Summaries (i.e., ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries). Moreover,

much of the assessed literature is based on these categories. In 1990,

most of the world’s $1.25 and $2 poor lived in low-income countries

(LICs). By 2008, the majority of the poor living on $1.25 and $2 (>70%)

resided in lower- and upper-middle-income countries (LMICs and UMICs),

in part because some populous LICs such as India, Nigeria, and Pakistan

grew in per capita income to MIC status (Sumner, 2010, 2012a). Estimates

suggest about 1 billion people currently living on less than $1.25 per

day in MICs and a second billion between $1.25 and $2, with an

additional 320 million and 170 million in LICs, respectively (Sumner,

2012b). About 70% of the poor subsisting on $1.25 per day live in rural

areas in the global South (IFAD, 2011), despite worldwide urbanization.

Yet, this poverty line understates urban poverty as it does not fully

account for the higher costs of food and non-food items in many urban

contexts (Mitlin and Satterthwaite, 2013). Of the approximately 2.4

billion living on less than $2 per day, half live in India and China. At the

same time, relative poverty is rising in HICs. Many European countries

face rapid increases in poverty, unemployment, and the number of

working poor due to recent austerity measures. For example, 20% of

Spanish citizens were ranked poor in 2009 (Ortiz and Cummins, 2013).

See also Chapter 23.

The shift in distribution of global poverty toward MICs and the increase

in relative poverty in HICs challenge the orthodox view that most of the

w

orld’s poorest people live in the poorest countries, and suggests that

substantial pockets of poverty persist in countries with higher levels of

average per capita income. Understanding this shift in the geography

of poverty and available social safety nets is vital for assessing climate

change impacts on poverty. To date, both climate finance and research

on climate impacts and vulnerabilities are directed largely toward LICs.

Less attention has been paid to poor people in MICs and HICs. In the

upper and lower MICs, the incidence of $2 per day poverty, despite

declines, remains as high as 60% and 20%, respectively (Sumner, 2012b).

Projections for 2030 suggest $2 per day poverty as high as 963 million

people in sub-Saharan Africa and 851 million in India (Sumner et al.,

2012; Edward and Sumner, 2013a). However, uncertainty is high in

terms of future growth and inequality trends; by 2030, $1.25 and $2

per day global poverty could be reduced to 300 million and 600 million

respectively or remain at or above current levels, including in stable

MICs (Edward and Sumner, 2013a). These future scenarios become more

uncertain if climate change impacts on people who are socially and

economically disadvantaged are taken into account or diversion of

resources from poverty reduction and social protection to mitigation

strategies is considered.

13.1.2.3. Spatial and Temporal Scales of Poverty

Poverty is also socially distributed, across spatial and temporal scales.

Not everybody is poor in the same way. Spatially, factors such as access

to and control over resources and institutional linkages from individuals

to the international level affect poverty distribution (Anderson and

Broch-Due, 2000; Murray, 2002; O’Laughlin, 2002; Rodima-Taylor, 2011).

Even at the household level, poverty differs between men and women

and age groups, yet data constraints impede systematic intra-household

analysis (Alkire and Santos, 2010). The distribution of poverty also varies

temporally, typically between chronic and transient poverty (Sen, 1981,

1999). Chronic poverty describes an individual deprivation, per capita

income, or consumption levels below the poverty line over many years

(Gaiha and Deolalikar, 1993; Jalan and Ravallion, 2000; Hulme and

Shepherd, 2003). Transient poverty denotes a temporary state of

deprivation, and is frequently seasonal and triggered by an individual’s

or household’s inability to maintain income or consumption levels in

times of shocks or crises (Jalan and Ravallion, 1998).

Individuals and households can fluctuate between different degrees of

poverty and shift in and out of deprivation, vulnerability, and well-being

(Leach et al., 1999; Little et al., 2008; Sallu et al., 2010). Yet, the most

disadvantaged often find themselves in poverty traps, or situations in

which escaping poverty becomes impossible without external assistance

due to unproductive or inflexible asset portfolios (Barrett and McPeak,

2006). A poverty trap can also be seen as a “critical minimum asset

threshold, below which families are unable to successfully educate their

children, build up their productive assets, and move ahead economically

over time” (Carter et al., 2007 p. 837). As of 2008, a total of 320 to 443

million of people were trapped in chronic poverty (Chronic Poverty

Research Centre, 2008), leading Sachs (2006) to label less than $1.25

per day poverty as a trap in itself. Poverty traps at the national level

are often related to poor governance, reduced foreign investment, and

conflict (see Chapters 10, 12).

802

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

13.1.3. Inequality and Marginalization

Specific livelihoods and poverty alone do not necessarily make people

vulnerable to weather events and climate. The socially and economically

disadvantaged and the marginalized are disproportionately affected by

the impacts of climate change and extreme events (robust evidence;

Kates, 2000; Paavola and Adger, 2006; Adger et al., 2007; Cordona et

al., 2012). The AR4 identified poor and indigenous peoples in North

America (Field et al., 2007) and in Africa (Boko et al., 2007) as highly

vulnerable. Vulnerability, or the propensity or predisposition to be

adversely affected (IPCC, 2012a) by climatic risks and other stressors (see

also Glossary), emerges from the intersection of different inequalities, and

uneven power structures, and hence is socially differentiated (Sen, 1999;

Banik, 2009; IPCC, 2012a). Vulnerability is often high among indigenous

peoples, women, children, the elderly, and disabled people who experience

multiple deprivations that inhibit them from managing daily risks and

shocks (Eriksen and O’Brien, 2007; Ayers and Huq, 2009; Boyd and

Juhola, 2009; Barnett and O’Neill, 2010; O’Brien et al., 2010; Petheram

et al., 2010) and may present significant barriers to adaptation.

Global income inequality has been relatively consistent since the late

1980s. In 2007, the top quintile of the world’s population received 83%

of the total income whereas the bottom quintile took in 1% (Ortiz and

Cummins, 2011). Since 2005, between-country inequality has been

falling more quickly and, consequently, has triggered a notable decline

in total global inequality in the last few years (Edward and Sumner,

2013b). However, within-country inequality is rising in Asia, especially

China, albeit from relatively low levels, and is falling in Latin America,

albeit from very high levels, while trends in sub-Saharan Africa are

difficult to discern regionally (Ravallion and Chen, 2012). Income

inequality is rising in many fast growing LICs and MICs (Dollar et al.,

2013; Edward and Sumner, 2013b). It is also growing in many HICs owing

to a combination of factors such as changing tax systems, privatization

of social services, labor market regulations, and technological change

(

OECD, 2011). The 2008 financial crisis, combined with climate change,

has further threatened economic growth in HICs, such as the UK, and

resources available for social policies and welfare systems (Gough,

2010). Recognizing how inequality and marginalization perpetuate

poverty is a prerequisite for climate-resilient development pathways

(see Section 13.4; Chapters 1, 20, 27).

13.1.4. Interactions between Livelihoods, Poverty,

Inequality, and Climate Change

This chapter opens its analytical lens from a conventional focus on

the poor in LICs as the prime victims of climate change to a broader

understanding of livelihood and poverty dynamics and inequalities,

revealing the highly unequal impacts of climate change. It highlights

the complex relationship between climate change and poverty. The

SREX recognizes that addressing structural inequalities that create and

sustain poverty and vulnerability (Huq et al., 2005; Schipper, 2007;

Lemos et al., 2007; Boyd and Juhola, 2009; Williams, 2010; Perch, 2011)

is a crucial precondition for confronting climate change (IPCC, 2012a).

If ignored, uneven social relations that disproportionally burden poor

people with climate change’s negative impacts provoke maladaptation

(Barnett and O’Neill, 2010).

Poverty and persistent inequality are the “most salient of the conditions

that shape climate-related vulnerability” (Ribot, 2010, p. 50). They affect

livelihood options and trajectories, and create conditions in which people

have few assets to liquidate in times of hardship or crisis (Mearns and

Norton, 2010). People who are poor and marginalized usually have the

least buffer to face even modest climate hazards and suffer most from

successive events with little time for recovery. They are the first to

experience asset erosion, poverty traps, and barriers and limits to

adaptation. As shown in Sections 13.2 and 13.3, climate change is an

additional burden to people in poverty (very high confidence), and it

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 13.2 | How important are climate change-driven impacts on poverty

compared to other drivers of poverty?

Climate change-driven impacts are one of many important causes of poverty. They often act as a threat multiplier,

meaning that the impacts of climate change compound other drivers of poverty. Poverty is a complex social and

political problem, intertwined with processes of socioeconomic, cultural, institutional, and political marginalization,

inequality, and deprivation, in low-, middle-, and even high-income countries. Climate change intersects with many

causes and aspects of poverty to worsen not only income poverty but also undermine well-being, agency, and a

sense of belonging. This complexity makes detecting and measuring attribution to climate change exceedingly

difficult. Even modest changes in seasonality of rainfall, temperature, and wind patterns can push transient poor

and marginalized people into chronic poverty as they lack access to credit, climate forecasts, insurance, government

support, and effective response options, such as diversifying their assets. Such shifts have been observed among

climate-sensitive livelihoods in high mountain environments, drylands, and the Arctic, and in informal settlements

and urban slums. Extreme events, such as floods, droughts, and heat waves, especially when occurring in a series,

can significantly erode poor people’s assets and further undermine their livelihoods in terms of labor productivity,

housing, infrastructure, and social networks. Indirect impacts, such as increases in food prices due to climate-related

disasters and/or policies, can also harm both rural and urban poor people who are net buyers of food.

803

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

w

ill force poor people from transient into chronic poverty and create

new poor (medium confidence).

The complex interactions among weather events and climate, dynamic

livelihoods, multidimensional poverty and deprivation, and persistent

inequalities, including gender inequalities, create an ever-shifting context

of risk. The SREX concluded that climate change, climate variability, and

extreme events synergistically add on to and often reinforce other

environmental, social, and political calamities (IPCC, 2012a). Despite

the recognition of these complex interactions, the literature shows no

single conceptual framework that captures them concurrently, and few

studies exist that overlay gradual climatic shifts or rapid-onset events

onto livelihood risks. Hence, explicit attention to how livelihood dynamics

interact with climatic and non-climatic stressors is useful for identifying

processes that push poor and vulnerable people onto undesirable

trajectories, trap them in destitution, or facilitate pathways toward

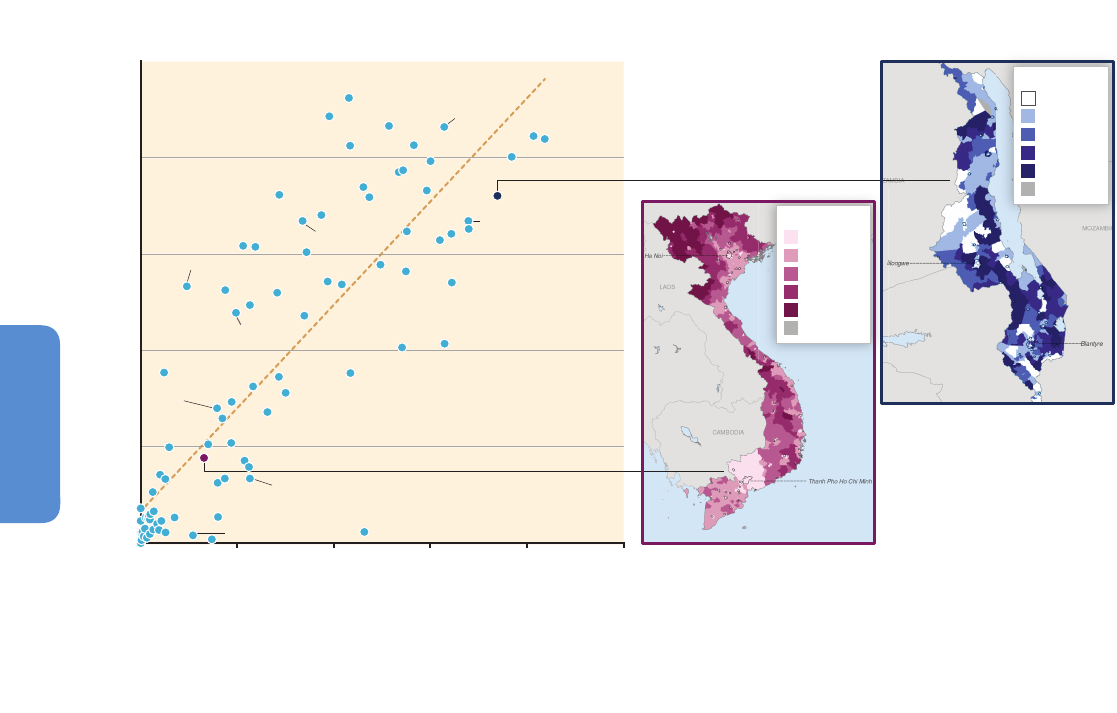

enhanced well-being. Figure 13-3 illustrates these dynamics as well as

critical thresholds in livelihood trajectories.

13.2. Assessment of Climate Change Impacts

on Livelihoods and Poverty

This section reviews the evidence and agreement about the relationships

among climate change, livelihoods, poverty, and inequality. Building on

deductive reasoning and theorized linkages about these dynamic

relationships, this section draws on a wide range of empirical case

studies and simulations to illustrate linkages across multiple scales,

contexts, and social and environmental processes and to assess impacts

of climate change. Although cases of observed impacts often rely on

qualitative data and at times lack methodological clarity in terms of

detection and attribution, they provide a vital evidence base for

conveying these complex relationships. This section first describes

observed impacts to date (Section 13.2.1) and then projected risks and

impacts (Section 13.2.2).

13.2.1. Evidence of Observed Climate Change Impacts

on Livelihoods and Poverty

Weather events and climate affect the lives and livelihoods of millions

of poor people (IPCC, 2012b). Even minor changes in precipitation

amount or temporal distribution, short periods of extreme temperatures,

or localized strong winds can harm livelihoods (Douglas et al., 2008;

Ostfeld, 2009; Midgley and Thuiller, 2011; Bele et al., 2013; Bryan et al.,

2013). Many such events remain unrecognized given that standard

climate observations typically report precipitation or temperature by

month, season, or year, thus obscuring changes that shape decision

making, for instance, in agriculture (Tennant and Hewitson, 2002;

Barron et al., 2003; Usman and Reason, 2004; Douglas et al., 2008;

Lacombe et al., 2012; Salack et al., 2012). This difficulty in detection and

attribution is compounded by a lack of long-term continuous and dense

networks of climate data in many LICs (UNECA, 2011). Felt experiences

of events such as drought, as shown among the Sumbanese in Eastern

Indonesia through phenomenological research on perceptions of

climatic phenomena, such as shade and dew (Orr et al., 2012), further

add to the complexity.

13.2.1.1. Impacts on Livelihood Assets and Human Capabilities

Climate change, climate variability, and extreme events interact with

numerous aspects of people’s livelihoods. This section presents empirical

evidence of impacts on natural, physical, financial, human, and social

and cultural assets (see also Chapters 22 to 29). Impacts on access to

assets, albeit important, are poorly documented in the literature, as are

impacts on power relations and active struggles in designing effective

and relational livelihood arrangements.

Weather events and climate affect natural assets on which certain

livelihoods depend directly, such as rivers, lakes, and fish stocks (robust

evidence; Thomas et al., 2007; Nelson and Stathers, 2009; Osbahr et al.,

2010; Bunce et al., 2010a,b; D’Agostino and Sovacool, 2011; see also

Chapters 3, 4, 5, 6, 30). During the 20th century, water temperatures

increased and winds decreased in Lake Tanganyika (Adrian et al., 2009;

Verburg and Hecky, 2009; Tierney et al., 2010). Since the late 1970s, a

drop in primary production and fish catches, a key protein source, has

been observed, and climate change may exceed the effects of overfishing

and other human impacts in this area (O’Reilly et al., 2003). The Middle

East and North Africa (MENA) face dwindling water resources due to

less precipitation and rising temperatures combined with mounting

water demand due to population and economic growth (Tekken and

Kropp, 2012), resulting in rapidly decreasing water availability that, in

2025, could be 30 to 70% less per person (Sowers et al., 2011). In MENA

(Sowers et al., 2011), the Andes and Himalayas (Orlove, 2009), the

Caribbean (Cashman et al., 2010), Australia (Alston, 2011), and in cities

(Satterthwaite, 2011), policy allocation often favors more affluent

consumers, at the expense of less powerful rural and/or poor users.

Weather events and climate also erode farming livelihoods (see Chapters

7, 9), via declining crop yields (Hassan and Nhemachena, 2008; Apata

et al., 2009; Sissoko et al., 2011; Sietz et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013), at times

compounded by increased pathogens, insect attacks, and parasitic weeds

(Stringer et al., 2007; Byg and Salick, 2009), and less availability of and

access to non-timber forest products (Hertel and Rosch, 2010; Nkem et

al., 2012) and medicinal plants and biodiversity (Van Noordwijk, 2010).

For agropastoral and mixed crop-livestock livelihoods, extreme high

temperatures threaten cattle (Hahn, 1997; Thornton et al., 2007; Mader,

2012; Nesamvuni et al., 2012); in Kenya, for instance, people may shift

from dairy to beef cattle and from sheep to goats (Kabubo-Mariara, 2008).

The most extreme form of erosion of natural assets is the complete

disappearance of people’s land on islands and in coastal regions

(McGranahan et al., 2007; Solomon et al., 2009), exacerbating livelihood

risks due to loss of economic and social assets (see Chapters 5, 29; Perch

and Roy, 2010). Densely populated coastal cities with high poverty such

as Alexandria and Port Said in Egypt (El-Raey et al., 1999), Cotonou in

Benin (Dossou and Glehouenou-Dossou, 2007), and Lagos and Port

Harcourt in Nigeria (Abam et al., 2000; Fashae and Onafeso, 2011) are

already affected by floods and at risk of submersion. Resettlements are

planned for the Limpopo River and the Mekong River Delta (de

Sherbinin et al., 2011) and small island states may become uninhabitable

(Burkett, 2011).

Damage to physical assets due to weather events and climate is well

documented for poor urban settlements, often built in risk-prone

804

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

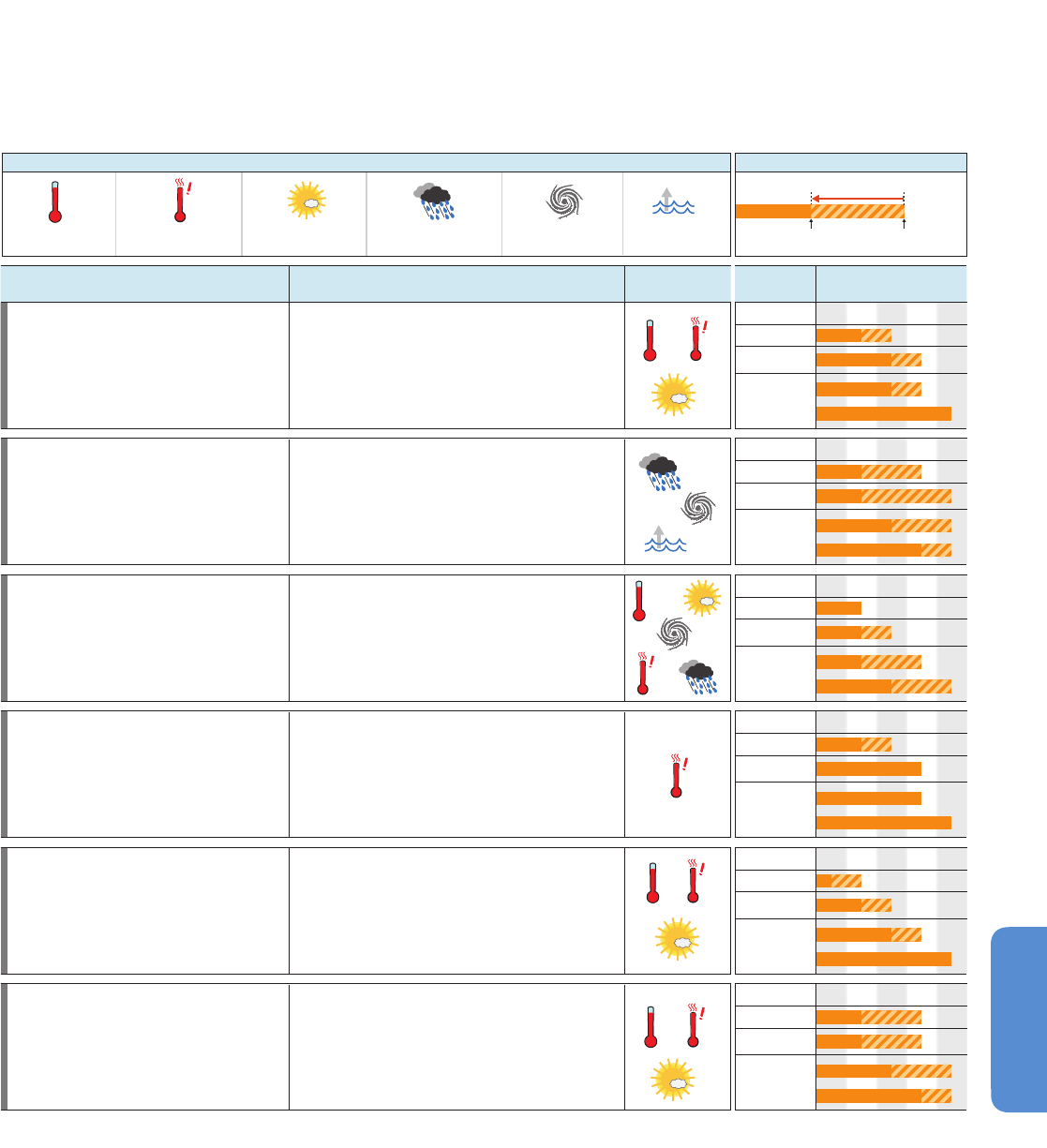

Convergence of multiple

stressors and shocks

Convergence of multiple

stressors and shocks

Convergence of multiple

stressors and shocks

Non-supportive

policy environment

Institutional &

Policy Reform

Current policy

responses

Potential policy

responses

Non-supportive

policy environment

Current policy

responses

Potential policy

responses

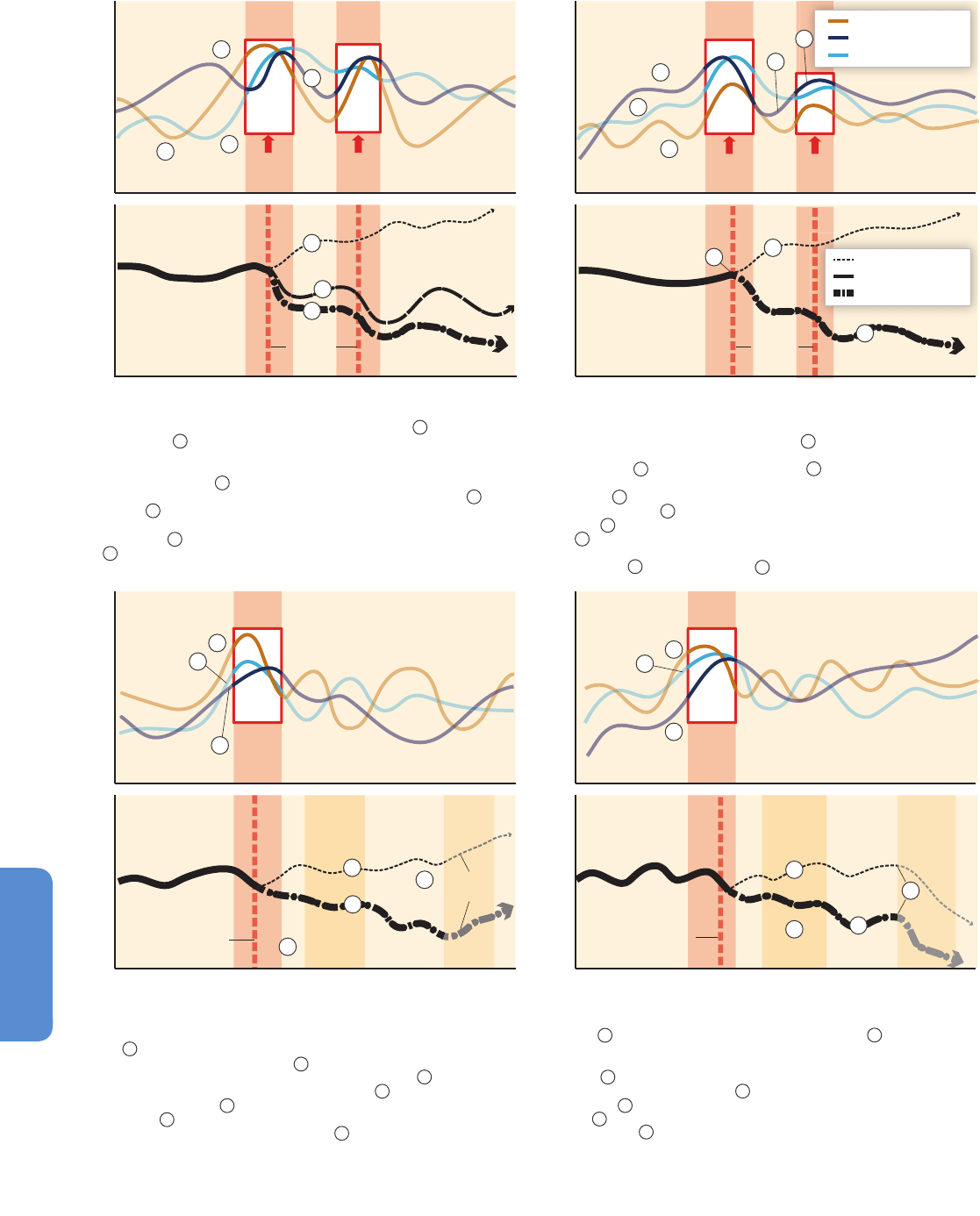

(a)

(b)

Intensity of stressors

Catastrophic

Negligible

Critical

thresholds

Critical

threshold

Livelihood condition

Vulnerable Resilient

Intensity of stressors

Catastrophic

Negligible

Livelihood condition

Vulnerable Resilient

(d)(c)

Intensity of stressors

Catastrophic

Negligible

Livelihood condition

Vulnerable Resilient

1

1

2

3

3

2

4

2

5

6

7

5

4

4

6

5

1

7

6

8

Convergence of multiple

stressors and shocks

4

6

7

5

Time Time

Time Time

Critical

thresholds

Climatic factors

Socioeconomic factors

Environmental factors

Some few households

Several households

Most households

Intensity of stressors

Catastrophic

Negligible

Livelihood condition

Vulnerable Resilient

Critical

threshold

R

ecent past Near future Recent past Near future

Recent past Near futureRecent past Near future

1

3

2

7

3

(a) Botswana’s drylands (Sallu et al., 2010). Over the past 30 years, rural households have

faced droughts, late onset and increased unpredictability of rainfall, and frost 1 , drying of Lake Xau,

and land degradation 2 . Households responded differently to these stressors, given their financial

and physical assets, diversification of and within livelihood activities, family relations, and

institutional and governmental support. Despite weakening of social networks and declining

livestock due to lack of water 3 , distinct livelihood trajectories emerged. “Accumulators” were

often able to benefit from crises, for instance through access to salaried employment 4 or new

hunting quotas 5 , while “dependent” households showed a degenerative trajectory, losing more

and more livelihood assets, and becoming reliant on governmental support after another period of

convergent stressors 6 . “Diversifiers” had trajectories fluctuating between vulnerable and resilient

states 7 .

(b) Coastal Bangladesh (Pouliotte et al., 2010). In the Sunderbans, a combination of

environmental and socioeconomic factors, out of which climatic stressors appear to play only a

minor role, have changed livelihoods: saltwater intrusion 1 due to the construction and poor

management of the Bangladeshi Coastal Embankment Project, the construction of a dam in India,

local water diversions 2 , and sea level rise and storm surges 3 . The convergence of these stressors

caused households to cross a critical threshold from rice and vegetable cultivation to saltwater

shrimp farming 4 . A strong export market and international donor and national government

support facilitated this shift 5 . However, increasing density of shrimp farming then triggered rising

disease levels 6 . Wealth and power started to become more concentrated among a few affluent

families 7 while livelihood options for the poorer households further diminished due to lacking

resources to grow crops in salinated water, the loss of grazing areas and dung from formerly

accessible rice fields 8 , and rising disease levels 6 .

(c) Mountain environments (McDowell and Hess, 2012). Indigenous Aymara farmers in

highland Bolivia face land scarcity, pervasive poverty, climate change, and lack of infrastructure due

in part to racism and institutional marginalization. The retreat of the Mururata glacier causes water

shortages 1 , compounded by the increased water requirements of cash crops on smaller and

smaller “minifundios” and market uncertainties 2 . High temperatures amplify evaporation, and

flash floods coupled with delayed rainfall cause irrigation canals to collapse 3 . The current policy

environment makes it difficult to access loans and obtain land titles 4 , pushing many farmers onto

downward livelihood trajectories 5 while those who can afford it invest in fruit and vegetable trees

at higher altitudes 6 . Sustained access to land, technical assistance, and irrigation infrastructure

would be effective policy responses to enhance well-being 7 .

(d) Urban flooding in Lagos (Adelekan, 2010). Flooding threatens the livelihoods of people

in Lagos, Nigeria, where >70 % live in slums. Increased severity in rainstorms, sea level rise, and

storm surges 1 coupled with the destruction of mangroves and wetlands 2 , disturb people’s jobs

as traders, wharf workers, and artisans, while destroying physical and human assets. Urban

management, infrastructure for water supply, and stormwater drainage have not kept up with

urban growth 3 . Inadequate policy responses, including uncontrolled land reclamation, make these

communities highly vulnerable to flooding 4 . Only some residents can afford sand and broken

sandcrete blocks 5 . Livelihood conditions in these slums are expected to further erode for most

households 6 . Given policy priorities for the construction of high-income residential areas, current

residents fear eviction 7 .

Figure 13-3 | Illustrative representation of four case studies that describe livelihood dynamics under simultaneous climatic, environmental, and socioeconomic stressors, shocks,

and policy responses – leading to differential livelihood trajectories over time. The red boxes indicate specific critical moments when stressors converge, threatening livelihoods

and well-being. Key variables and impacts numbered in the illustrations correspond to the developments described in the captions.

805

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

f

loodplains and hillsides susceptible to erosion and landslides. Impacts

include homes destroyed by flood water and disrupted water and

sanitation services. Flooding has adversely affected large cities in Africa

(Douglas et al., 2008) and Latin America (Hardoy and Pandiella, 2009;

Hardoy et al., 2011), in predominantly dense informal settlements due

to inadequate drainage, and health infrastructure (UNDP, 2011c). Yet,

upper-middle- and high-income households living in flood-prone areas

or high-risk slopes frequently can afford insurance and lobby for

protective policies, in contrast to poor residents (Hardoy and Pandiella,

2009). Loss of physical assets in poor areas after disasters is often

followed by displacement due to loss of property (Douglas et al., 2008).

Increasing flash floods attributed to climate change (Sudmeier-Rieux et

al., 2012) have severely damaged terraces, orchards, roads, and stream

embankments in the Himalayas (Azhar-Hewitt and Hewitt, 2012; Hewitt

and Mehta, 2012).

Erosion of financial assets as a result of climatic stressors include losses

of farm income and jobs (Hassan and Nhemachena, 2008; Iwasaki et al.,

2009; Alderman, 2010; Jabeen et al., 2010; Alston, 2011) and increased

costs of living such as higher expenses for funerals (Gabrielsson et al.,

2012). In South and Central America, more than 600 weather and extreme

events occurred 2000–2013, resulting in 13,500 fatalities, 52.6 million

people affected, and economic losses of US$45.3 billion (www.emdat.be).

Income losses due to weather events mean less money for agricultural

inputs (seeds, equipment), school tuition, uniforms, and books, and

health expenses throughout the year (Thomas et al., 2007). Flooding in

informal settlements in Lagos undermines job opportunities (Adelekan,

2010).

Equally important, albeit frequently overlooked, is the damage to

human assets as a result of weather events and climate, such as food

insecurity, undernourishment, and chronic hunger due to failed crops

(medium evidence) (Patz et al., 2005; Funk et al., 2008; Zambian

Government, 2011; Gentle and Maraseni, 2012) or spikes in food prices

most severely felt among poor urban populations (Ahmed et al., 2009;

Hertel and Rosch, 2010). During the Ethiopian drought (1998–2000)

and Hurricane Mitch in Nicaragua (1998), poorer households tended to

engage in asset smoothing, reducing their consumption to very low

levels to protect their assets, whereas wealthier households sold assets

and smoothed consumption (Carter et al., 2007). In such cases, poor

people further erode nutritional levels and human health while holding

on to their limited assets. Dehydration, heat stroke, and heat exhaustion

from exposure to heat waves undermine people’s ability to carry out

physical work outdoors and indoors (Semenza et al., 1999; Kakota et al.,

2011). Psychological effects from extreme events include sleeplessness,

anxiety and depression (Byg and Salick, 2009; Keshavarz et al., 2013),

loss of sense of place and belonging (Tschakert et al., 2011; Willox et

al., 2012), and suicide (Caldwell et al., 2004; Alston, 2011) (see also

Chapter 11 and Box CC-HS).

Finally, weather events and climate also erode social and cultural assets.

In some contexts, climatic and non-climatic stressors and changing

trends disrupt informal social networks of the poorest, elderly, women,

and women-headed households, preventing mobilization of labor and

reciprocal gifts (Osbahr et al., 2008; Buechler, 2009) as well as formal

social networks, including social assistance programs (Douglas et al.,

2008). Indigenous peoples (see Chapter 12) witness their cultural points

o

f reference disappearing (Ford, 2009; Bell et al., 2010; Green et al.,

2010).

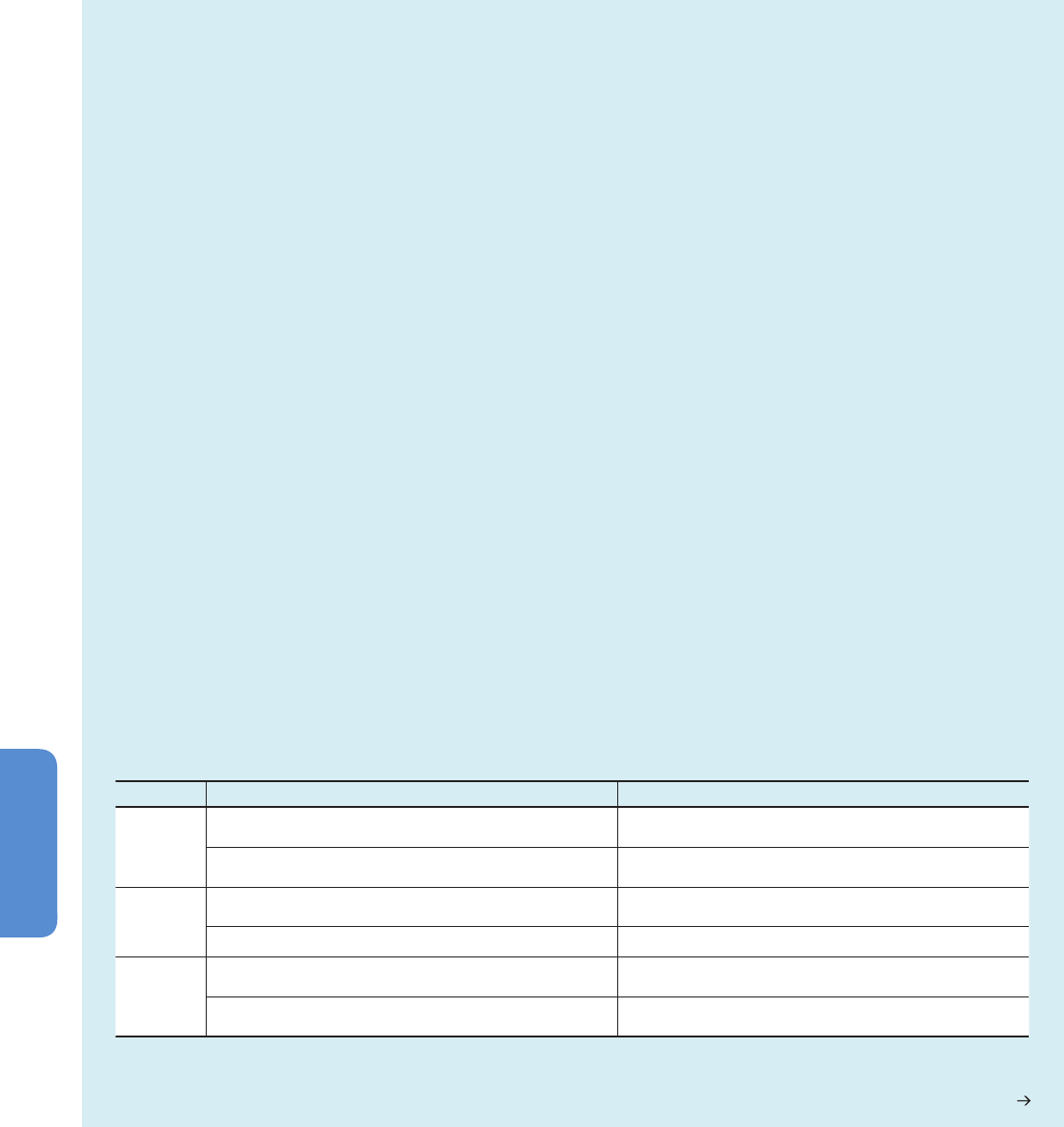

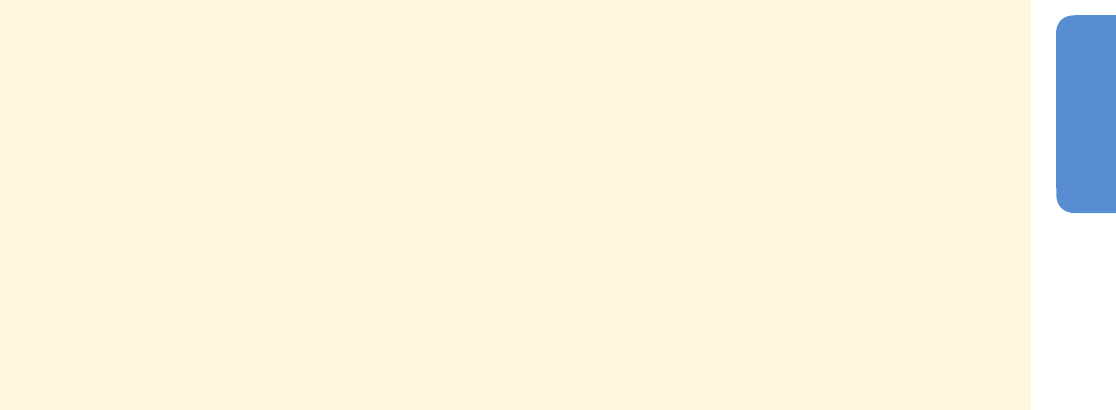

13.2.1.2. Impacts on Livelihood Dynamics and Trajectories

Weather events and climate also affect livelihood trajectories and

dynamics in livelihood decision making, often in conjunction with cross-

scalar socioeconomic, institutional, or political stressors. Shifting in and

out of hardship and well-being on a seasonal basis is not uncommon.

To a large extent, the shifts from coping and hardship to recovery are

driven by annual and interannual climate variability, but may become

exacerbated by climate change. Figure 13-4 illustrates seasonal livelihood

sensitivity for the Lake Victoria Basin in East Africa (Gabrielsson et al.,

2012).

Shifts in livelihoods often occur due to changing climate trends, linked

to a series of environmental, socioeconomic, and political stressors

(robust evidence). Farmers may change their crop choices instead of

abandoning farming (Kurukulasuriya and Mendelsohn, 2007) or take on

more lucrative income-generating activities (see Figure 13-3). Uncertainty

about West Africa’s rainy season threatens small-scale farming and water

management (Yengoh et al., 2010a,b; Armah et al., 2011; Karambiri et

al., 2011; Lacombe et al., 2012). Around Mali’s drying Lake Faguibine,

livelihoods shifted from water-based to agro-sylvo-pastoral systems, as

a direct impact of lower rainfall and more frequent and more severe

droughts (Brockhaus and Djoudi, 2008). Diverse indigenous groups in

Russia have changed their livelihoods as result of Soviet legacy and

climate change; for example, many Viliui Sakha have abandoned cow-

keeping due to youth out-migration, growing access to consumer goods,

and seasonal changes in temperature, rainfall, and snow (Crate, 2013).

Under certain converging shocks and stressors, people adopt entirely

new livelihoods. In South Africa, higher precipitation uncertainty raised

reliance on livestock and poultry rather than crops alone in 80% of

households interviewed (Thomas et al., 2007). In southern Africa and

India, people migrated to the coasts, switching from climate-sensitive

farming to marine livelihoods (Coulthard, 2008; Bunce et al., 2010a,b).

After Hurricane Stan (2005), land-poor coffee farmers in Chiapas, Mexico,

turned from specializing in coffee to being day laborers and subsistence

farmers (Eakin et al., 2012).

13.2.1.3. Impacts on Poverty Dynamics:

Transient and Chronic Poverty

Limited evidence documents the extent to which climate change intersects

with poverty dynamics, yet there is high agreement that shifts from

transient to chronic poverty due to weather and climate are occurring,

especially after a series of weather or extreme events (Scott-Joseph,

2010). Households in transient poverty may become chronically poor

due to a lack of effective response options to weather events and

climate, compared with more affluent households (see Figure 13-3).

Often, multiple deprivations drive these shifts, with socially and

economically marginalized groups particularly prone to slipping into

chronic poverty. Women-headed households, children, people in informal

settlements (see Chapter 8), and indigenous communities are particularly

at risk, owing to compounding stressors such as lack of governmental

806

Chapter 13 Livelihoods and Poverty

13

support, urban infrastructure, and insecure land tenure (see Section

13.2.1.5 and Chapter 12).

Poor people in urban areas in LICs and MICs in Africa, Asia, and Latin

America may slip from transient to chronic poverty given the combination

of population growth and flooding threats in low-elevation cities and

water stress in drylands (Balk et al., 2009) along with other multiple

deprivations (Mitlin and Satterthwaite, 2013). Poverty shifts also occur in

response to food price increases, though the strength of the relationship

between weather events and climate and food prices is still debated

(see Chapter 7 and Section 13.3.1.4). Poor households in urban and rural

areas are particularly at risk when they are almost exclusively net buyers

of food (Cranfield et al., 2007; Cudjoe et al., 2010; Ruel et al., 2010).

Misselhorn (2005) showed in a meta-study of 49 cases of food insecurity

in southern Africa that climatic drivers and poverty were the two

dominant and interacting causal factors. Poor pastoralists have collapsed

into chronic poverty when livestock assets have been lost (Thornton et

al., 2007). In rural areas, restricted forest access may exacerbate poverty

among already income-poor and elderly households who rely on forest

resources to respond to climatic shocks (Fisher et al., 2010). Yet, many

such shifts remain underexplored, incompletely captured in poverty data

and adaptation monitoring. The bulk of evidence in the literature is

oriented toward extreme events, rapid-onset disasters, and subsequent

impacts on livelihoods and poor people’s lives. Subtle changes are rarely

tracked, making quantification of long-term trends and detection of

impacts difficult.

13.2.1.4. Poverty Traps and Critical Thresholds

Poverty traps arise when climate change, variability, and extreme events

keep poor people poor and make some poor even poorer. Yet, attribution

remains a challenge. Among disadvantaged people in urban areas,

poverty traps are reported especially for wage laborers who erode their

financial capital due to increases in food prices (Ahmed et al., 2009;

Hertel and Rosch, 2010) and for those in informal settlements exposed

to floods and landslides (Hardoy and Pandiella, 2009). In rural areas,

poverty traps are reported when climate change impacts on poor people

persist over decades, such as through environmental degradation and

recurring stress on ecosystems in the Sahel (Kates, 2000; Hertel and

Rosch, 2010; Sissoko et al., 2011; UNCCD, 2011), or when people are

unable to rebuild assets after a series of stresses (Eriksen and O’Brien,

2007; Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2008; Sallu et al., 2010). Poverty traps and

destitution are also described in pastoralist systems, triggered through

droughts, restricted mobility owing to conflict and insecurity, adverse

terms of trade, and the conversion of grazing areas to agricultural land,

A

P

R

I

L

S

E

P

T

E

M

B

E

R

A

U

G

U

S

T

J

U

L

Y

J

U

N

E

M

A

Y

J

A

N

U

A

R

Y

F

E

B

R

U

A

R

Y

M

A

R

C

H

O

C

T

O

B

E

R

N

O

V

E

M

B

E

R

D

E

C

E

M

B

E

R

P

l

a

n

t

s

o

r

g

h

u

m

C

l

e

a

r

p

l

o

t

s

,

P

l

o

w

l

a

n

d

P

l

a

n

t

m

a

t

u

r

i

n

g

c

r

o

p

s

,

w

e

e

d

v

e

g

e

t

a

b

l

e

s

2

n

d

w

e

e

d

i

n

g

1

s

t

w

e

e

d

i

n

g

P

l

a

n

t

m

a

i

z

e

a

n

d

c

a

s

s

a

v

a

b

u

r

n

w

e

e

d

s

m

a

k

e

r

o

p

e

s

,

h

a

r

v

e

s

t

v

e

g

e

t

a

b

l

e

s

P

l

a

n

t

a

n

d

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

o

u

s

h

a

r

v

e

s

t

i

n

g

o

f

c

r

o

p

s

C

O

P

I

N

G

C

O

P

I

N

G

H

A

R

D

S

H

I

P

R

E

C

O

V

E

R

Y

H

A

R

D

S

H

I

P

C

O

P

I

N

G

1

s

t

m

a

i

z

e

h

a

r

v

e

s

t

E

y

e

I

n

f

e

c

t

i

o

n

M

e

a

s

l

e

s

M

a

l

a

r

i

a

D

i

a

r

r

h

e

a

P

n

e

u

m

o

n

i

a

C

o

u

g

h

i

n

g

T

y

p

h

o

i

d

M

a

l

a

r

i

a

M

a

l

a

r

i

a

E

y

e

i

n

f

e

c

t

i

o

n

M

a

l

a

r

i

a

C

o

n

s

t

i

p

a

t

i

o

n

C

h

o

l

e

r

a

P

n

e

u

m

o

n

i

a

I

n

fl

u

e

n

z

a

B

i

l

h

a

r

z

i

a

N

o

r

a

i

n

,

h

o

t

,

w

i

n

d

y

I

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

r

a

i

n

f

a

l

l

,

h

o

t

H

e

a

v

y

r

a

i

n

f

a

l

l

,

c

o

o

l

e

r

,

c

o

l

d

a

t

n

i

g

h

t

c

o

l

d

a

t

n

i

g

h

t

O

n

s

e

t

o

f

s

h

o

r

t

r

a

i

n

s

,

E

r

r

a

t

i

c

d

r

i

z

z

l

e

s

,

h

o

t

,

w

i

n

d

y

N

o

r

a

i

n

,

r

i

s

i

n

g

t

e

m

p

e

r

a

t

u

r

e

N

o

r

a

i

n

,

c

o

o

l

E

r

r

a

t

i

c

d

r

i

z

z

l

e

s

,

w

a

r

m

D

r

i

z

z

l

e

s

,

r

i

s

i

n

g

t

e

m

p

e

r

a

t

u

r

e

I

r

r

e

g

u

l

a

r

r

a

i

n

f

a

l

l

,

c

o

o

l

e

r

,

w

i

n

d

y

m

o

d

e

r

a

t

e

l

y

h

o

t

O

n

s

e

t

o

f

l

o

n

g

r

a

i

n

s

,

D

r

i

z

z

l

e

s

,

h

o

t

Climate

Farm work

Diseases

Figure 13-4 | Seasonal sensitivity of livelihoods to climatic and non-climatic stressors for one calendar year, based on experiences of smallholder farmers in the Lake Victoria

Basin in Kenya and Tanzania (Gabrielsson et al., 2012).

807

Livelihoods and Poverty Chapter 13

13

s

uch as for biofuel production (Eriksen and Lind, 2009; Homewood, 2009;

Eriksen and Marin, 2011). Other poverty traps result from heavy debt