SPM.1.1. Observed changes in the climate system

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, and sea level has risen. {1.1}

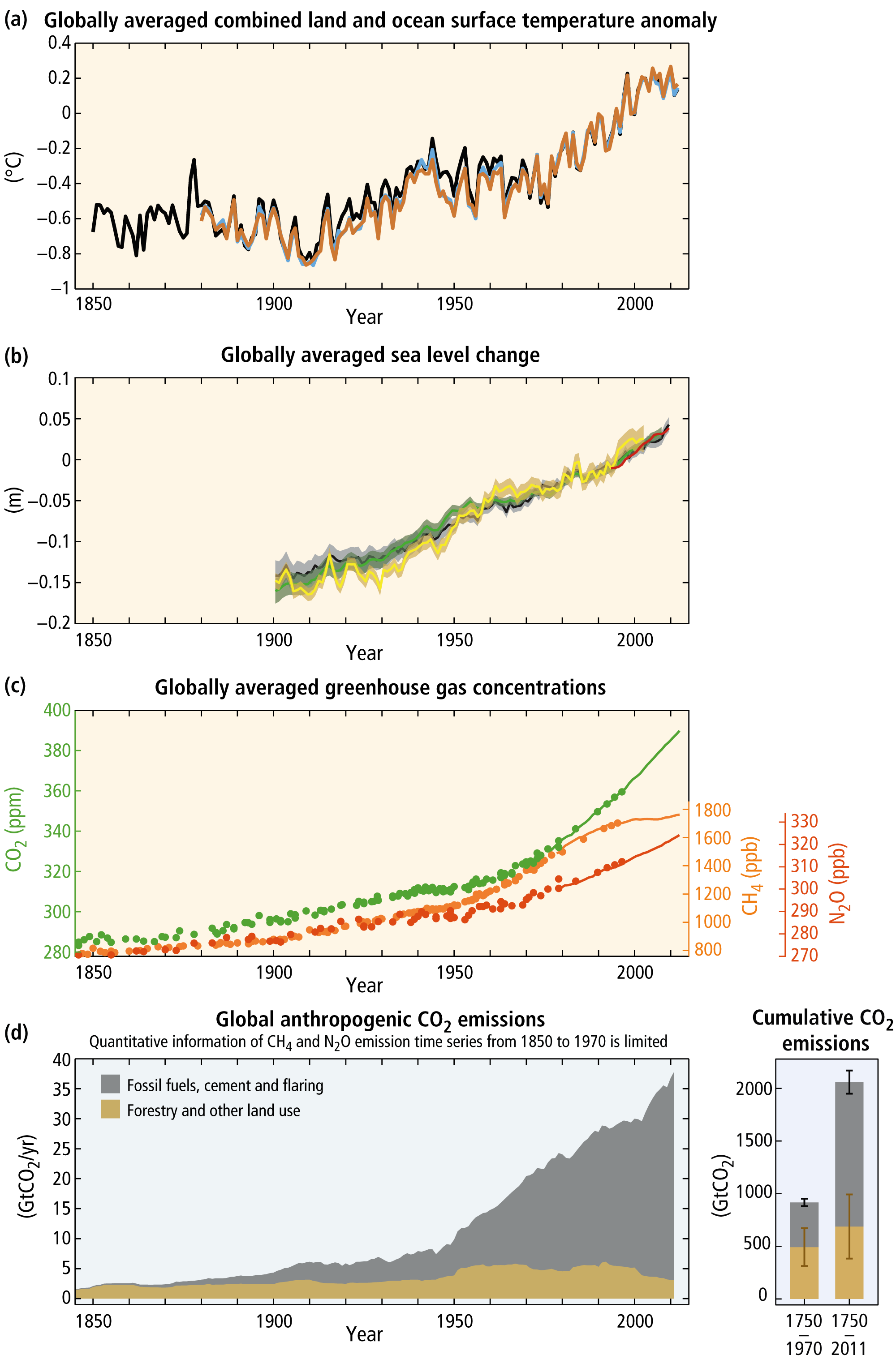

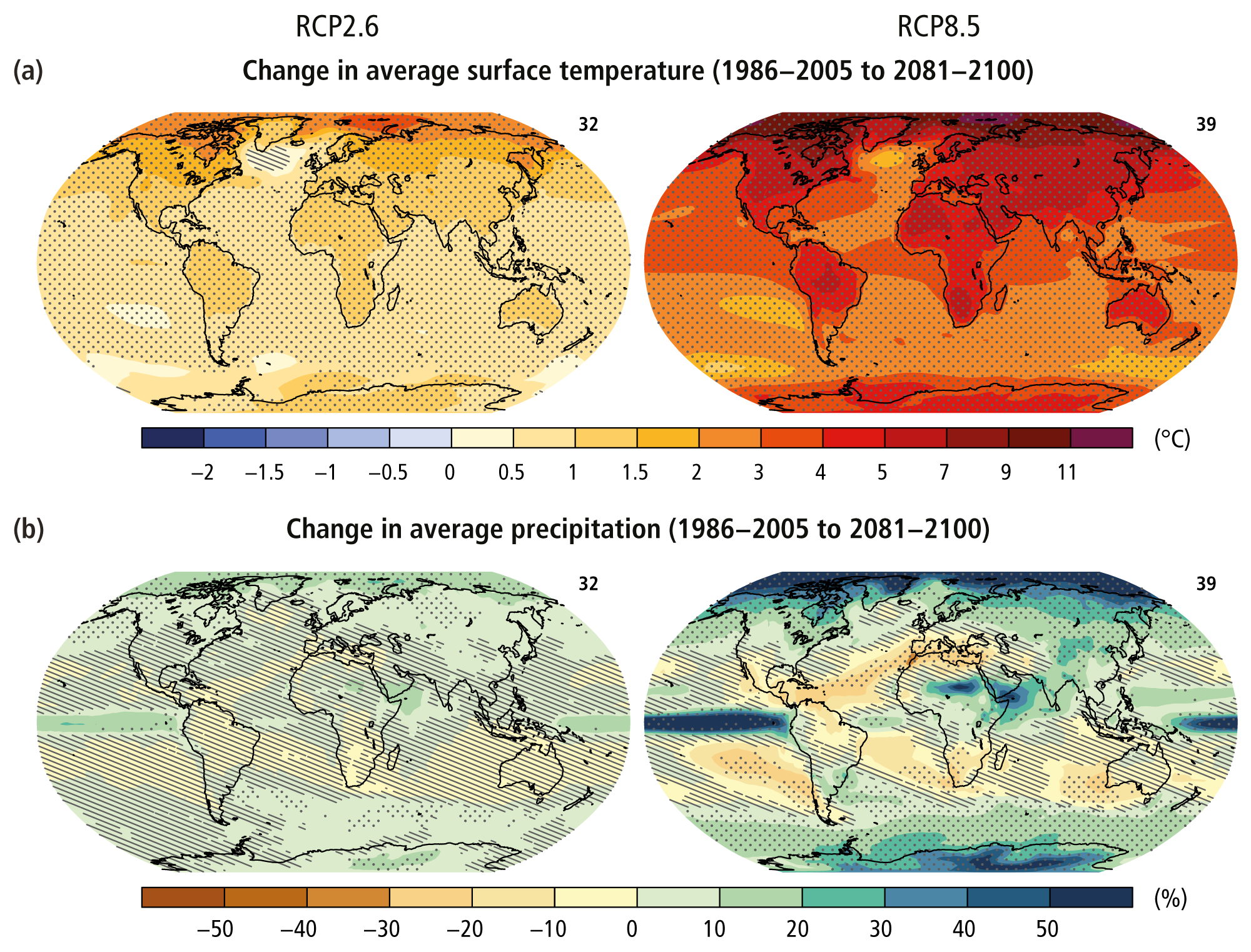

Each of the last three decades has been successively warmer at the Earth’s surface than any preceding decade since 1850. The period from 1983 to 2012 was likely the warmest 30-year period of the last 1400 years in the Northern Hemisphere, where such assessment is possible (medium confidence). The globally averaged combined land and ocean surface temperature data as calculated by a linear trend show a warming of 0.85 [0.65 to 1.06] °C 2 over the period 1880 to 2012, when multiple independently produced datasets exist (Figure SPM.1a). {1.1.1, Figure 1.1}

In addition to robust multi-decadal warming, the globally averaged surface temperature exhibits substantial decadal and interannual variability (Figure SPM.1a). Due to this natural variability, trends based on short records are very sensitive to the beginning and end dates and do not in general reflect long-term climate trends. As one example, the rate of warming over the past 15 years (1998–2012; 0.05 [–0.05 to 0.15] °C per decade), which begins with a strong El Niño, is smaller than the rate calculated since 1951 (1951–2012; 0.12 [0.08 to 0.14] °C per decade). {1.1.1, Box 1.1}

Ocean warming dominates the increase in energy stored in the climate system, accounting for more than 90% of the energy accumulated between 1971 and 2010 (high confidence), with only about 1% stored in the atmosphere. On a global scale, the ocean warming is largest near the surface, and the upper 75 m warmed by 0.11 [0.09 to 0.13] °C per decade over the period 1971 to 2010. It is virtually certain that the upper ocean (0−700 m) warmed from 1971 to 2010, and it likely warmed between the 1870s and 1971. {1.1.2, Figure 1.2}

Averaged over the mid-latitude land areas of the Northern Hemisphere, precipitation has increased since 1901 (medium confidence before and high confidence after 1951). For other latitudes, area-averaged long-term positive or negative trends have low confidence. Observations of changes in ocean surface salinity also provide indirect evidence for changes in the global water cycle over the ocean (medium confidence). It is very likely that regions of high salinity, where evaporation dominates, have become more saline, while regions of low salinity, where precipitation dominates, have become fresher since the 1950s. {1.1.1, 1.1.2}

Since the beginning of the industrial era, oceanic uptake of CO2 has resulted in acidification of the ocean; the pH of ocean surface water has decreased by 0.1 (high confidence), corresponding to a 26% increase in acidity, measured as hydrogen ion concentration. {1.1.2}

Over the period 1992 to 2011, the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets have been losing mass (high confidence), likely at a larger rate over 2002 to 2011. Glaciers have continued to shrink almost worldwide (high confidence). Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover has continued to decrease in extent (high confidence). There is high confidence that permafrost temperatures have increased in most regions since the early 1980s in response to increased surface temperature and changing snow cover. {1.1.3}

The annual mean Arctic sea-ice extent decreased over the period 1979 to 2012, with a rate that was very likely in the range 3.5 to 4.1% per decade. Arctic sea-ice extent has decreased in every season and in every successive decade since 1979, with the most rapid decrease in decadal mean extent in summer (high confidence). It is very likely that the annual mean Antarctic sea-ice extent increased in the range of 1.2 to 1.8% per decade between 1979 and 2012. However, there is high confidence that there are strong regional differences in Antarctica, with extent increasing in some regions and decreasing in others. {1.1.3, Figure 1.1}

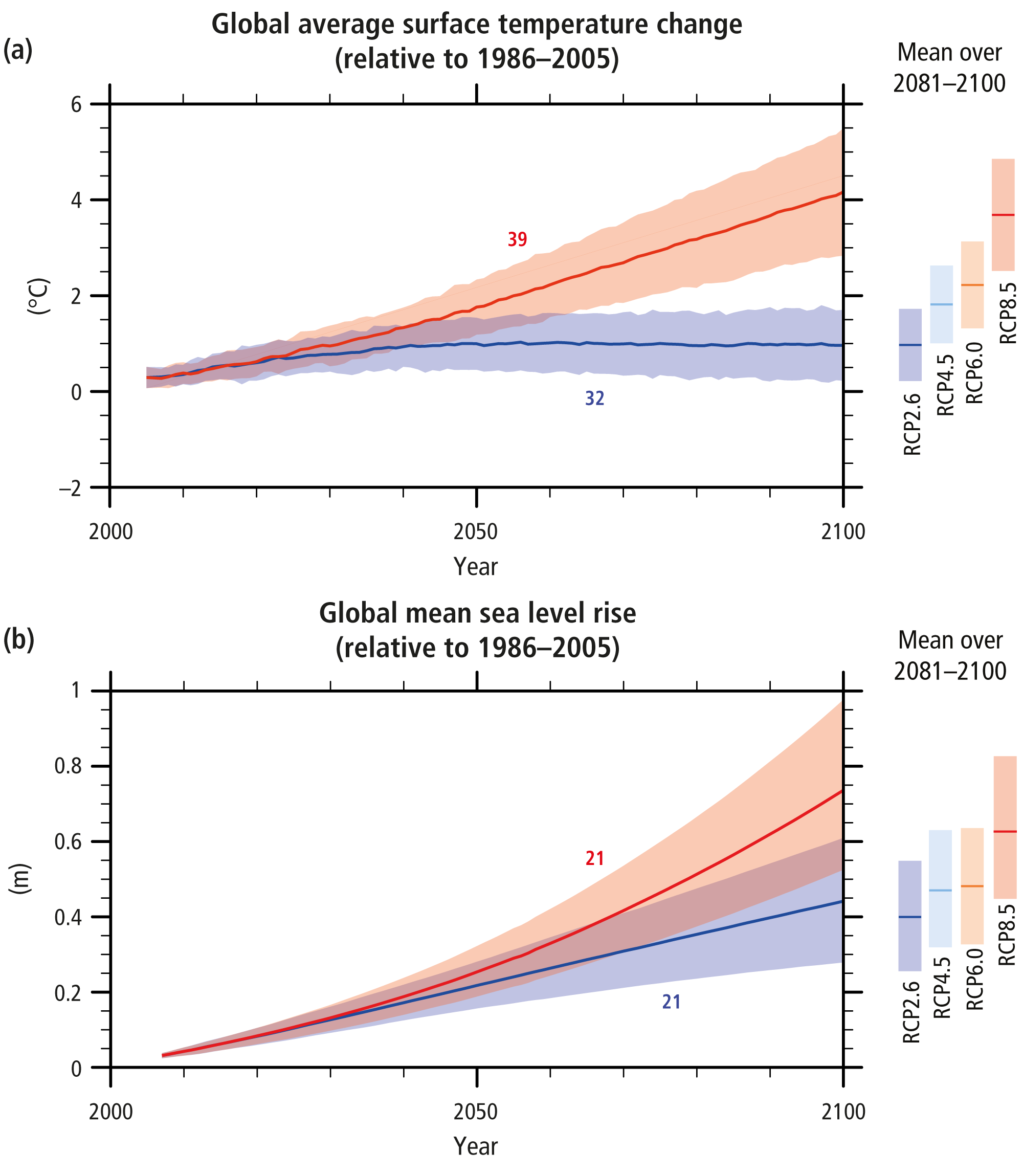

Over the period 1901 to 2010, global mean sea level rose by 0.19 [0.17 to 0.21] m (Figure SPM.1b). The rate of sea level rise since the mid-19th century has been larger than the mean rate during the previous two millennia (high confidence). {1.1.4, Figure 1.1}

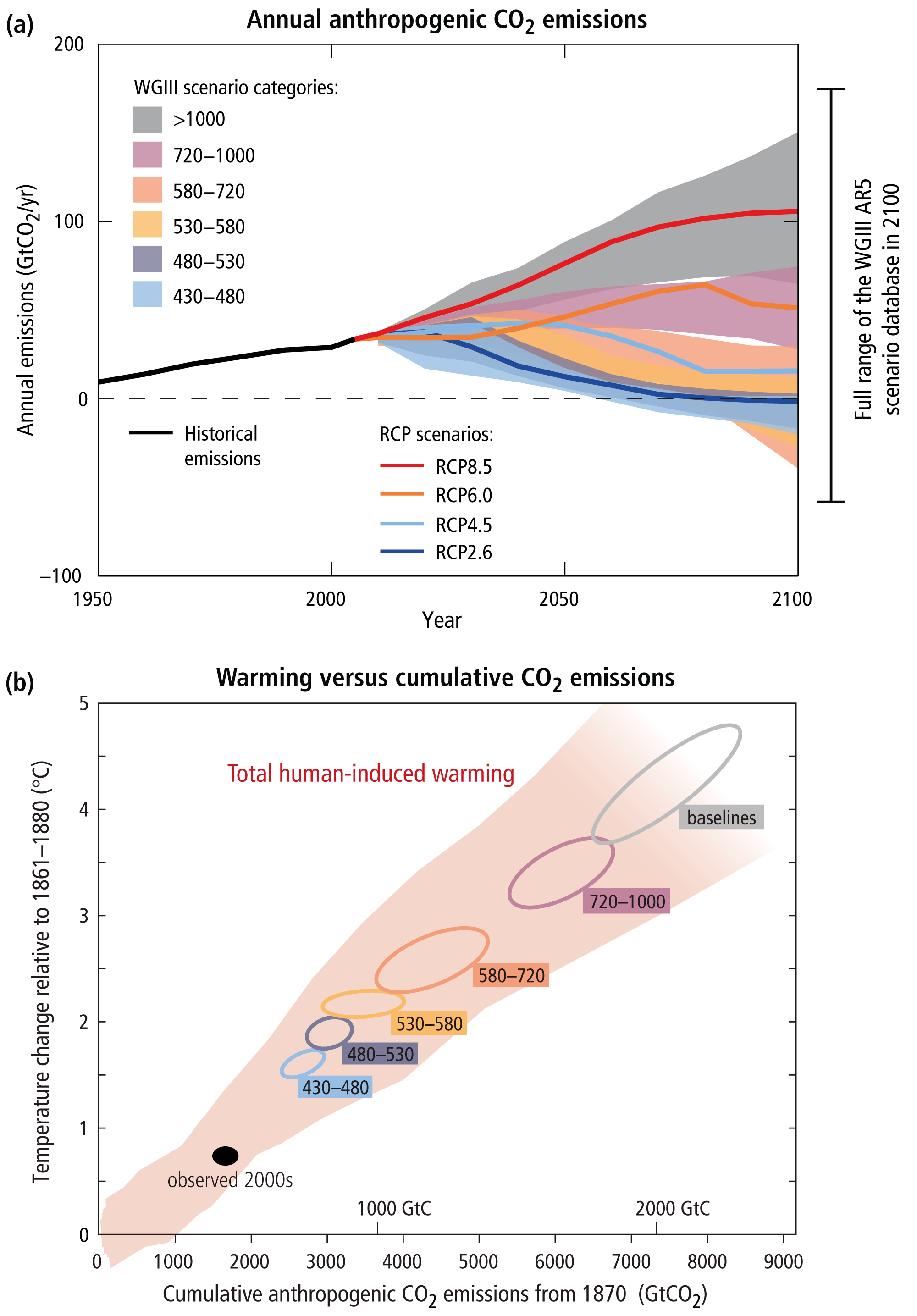

EditFigure SPM.1 | The complex relationship between the observations (panels a, b, c, yellow background) and the emissions (panel d, light blue background) is addressed in Section 1.2 and Topic 1. Observations and other indicators of a changing global climate system. Observations: (a) Annually and globally averaged combined land and ocean surface temperature anomalies relative to the average over the period 1986 to 2005. Colours indicate different data sets. (b) Annually and globally averaged sea-level change relative to the average over the period 1986 to 2005 in the longest-running dataset. Colours indicate different data sets. All datasets are aligned to have the same value in 1993, the first year of satellite altimetry data (red). Where assessed, uncertainties are indicated by coloured shading. (c) Atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2, green), methane (CH4, orange), and nitrous oxide (N2O, red) determined from ice core data (dots) and from direct atmospheric measurements (lines). Indicators: (d) Global anthropogenic CO2 emissions from forestry and other land use as well as from burning of fossil fuel, cement production, and flaring. Cumulative emissions of CO2 from these sources and their uncertainties are shown as bars and whiskers, respectively, on the right hand side. The global effects of the accumulation of CH4 and N2O emissions are shown in panel c. Greenhouse gas emission data from 1970 to 2010 are shown in Figure SPM.2. {Figures 1.1, 1.3, 1.5}

SPM.1.2. Causes of climate change

Anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have increased since the pre-industrial era, driven largely by economic and population growth, and are now higher than ever. This has led to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years. Their effects, together with those of other anthropogenic drivers, have been detected throughout the climate system and are extremely likely to have been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. {1.2, 1.3.1}

Anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions since the pre-industrial era have driven large increases in the atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) (Figure SPM.1c). Between 1750 and 2011, cumulative anthropogenic CO2 emissions to the atmosphere were 2040 ± 310 GtCO2. About 40% of these emissions have remained in the atmosphere (880 ± 35 GtCO2); the rest was removed from the atmosphere and stored on land (in plants and soils) and in the ocean. The ocean has absorbed about 30% of the emitted anthropogenic CO2, causing ocean acidification. About half of the anthropogenic CO2 emissions between 1750 and 2011 have occurred in the last 40 years (high confidence) (Figure SPM.1d). {1.2.1, 1.2.2}

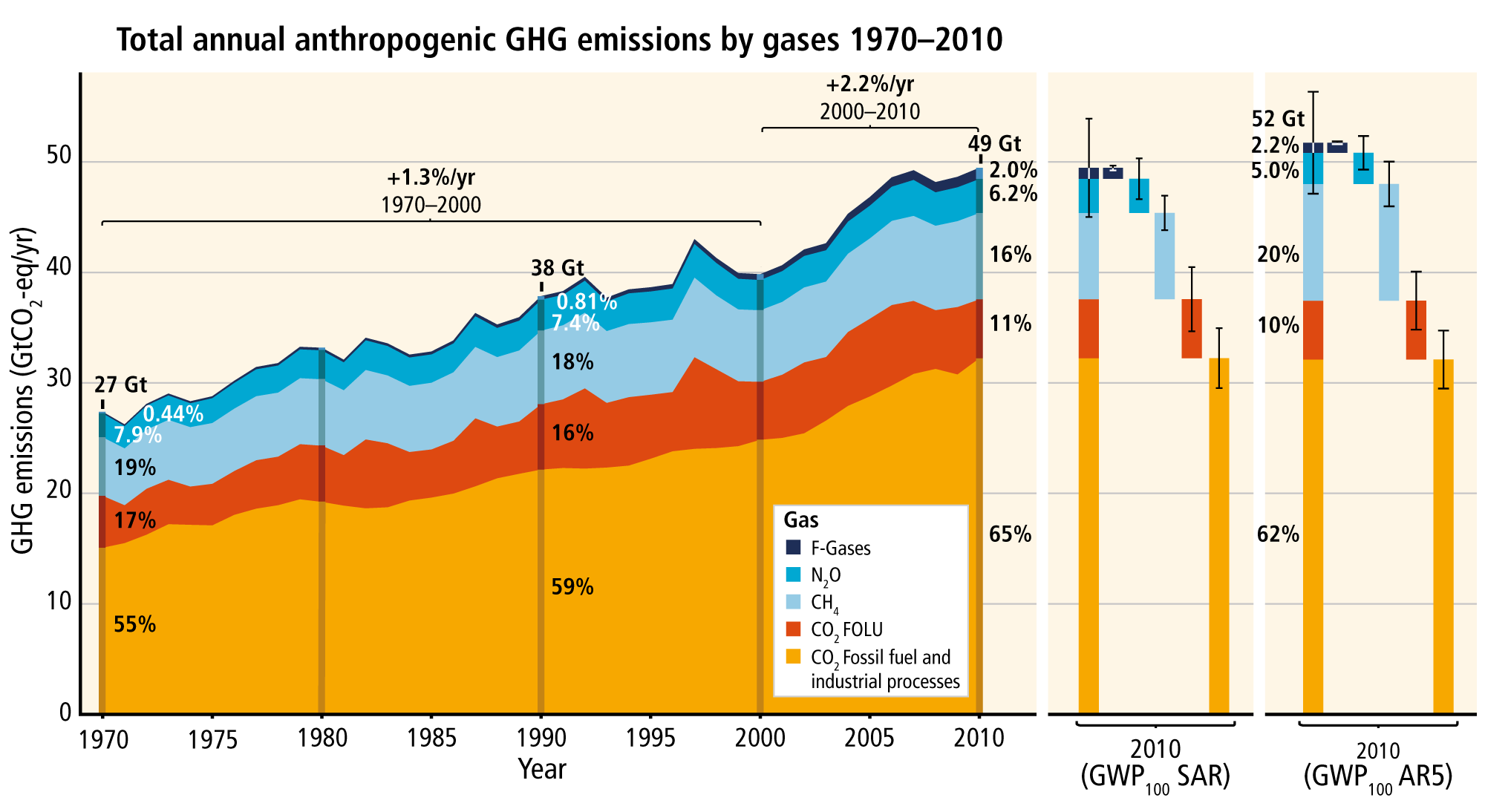

Figure SPM.2 | Total annual anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (gigatonne of CO2-equivalent per year, GtCO2-eq/yr) for the period 1970 to 2010 by gases: CO2 from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes; CO2 from Forestry and Other Land Use (FOLU); methane (CH4); nitrous oxide (N2O); fluorinated gases covered under the Kyoto Protocol (F-gases). Right hand side shows 2010 emissions, using alternatively CO2-equivalent emission weightings based on IPCC Second Assessment Report (SAR) and AR5 values. Unless otherwise stated, CO2-equivalent emissions in this report include the basket of Kyoto gases (CO2, CH4, N2O as well as F-gases) calculated based on 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP100) values from the SAR (see Glossary). Using the most recent GWP100 values from the AR5 (right-hand bars) would result in higher total annual GHG emissions (52 GtCO2-eq/yr) from an increased contribution of methane, but does not change the long-term trend significantly. {Figure 1.6, Box 3.2}

Total anthropogenic GHG emissions have continued to increase over 1970 to 2010 with larger absolute increases between 2000 and 2010, despite a growing number of climate change mitigation policies. Anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2010 have reached 49 ± 4.5 GtCO2-eq/yr3. Emissions of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes contributed about 78% of the total GHG emissions increase from 1970 to 2010, with a similar percentage contribution for the increase during the period 2000 to 2010 (high confidence) (Figure SPM.2). Globally, economic and population growth continued to be the most important drivers of increases in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion. The contribution of population growth between 2000 and 2010 remained roughly identical to the previous three decades, while the contribution of economic growth has risen sharply. Increased use of coal has reversed the long‐standing trend of gradual decarbonization (i.e., reducing the carbon intensity of energy) of the world’s energy supply (high confidence). {1.2.2}

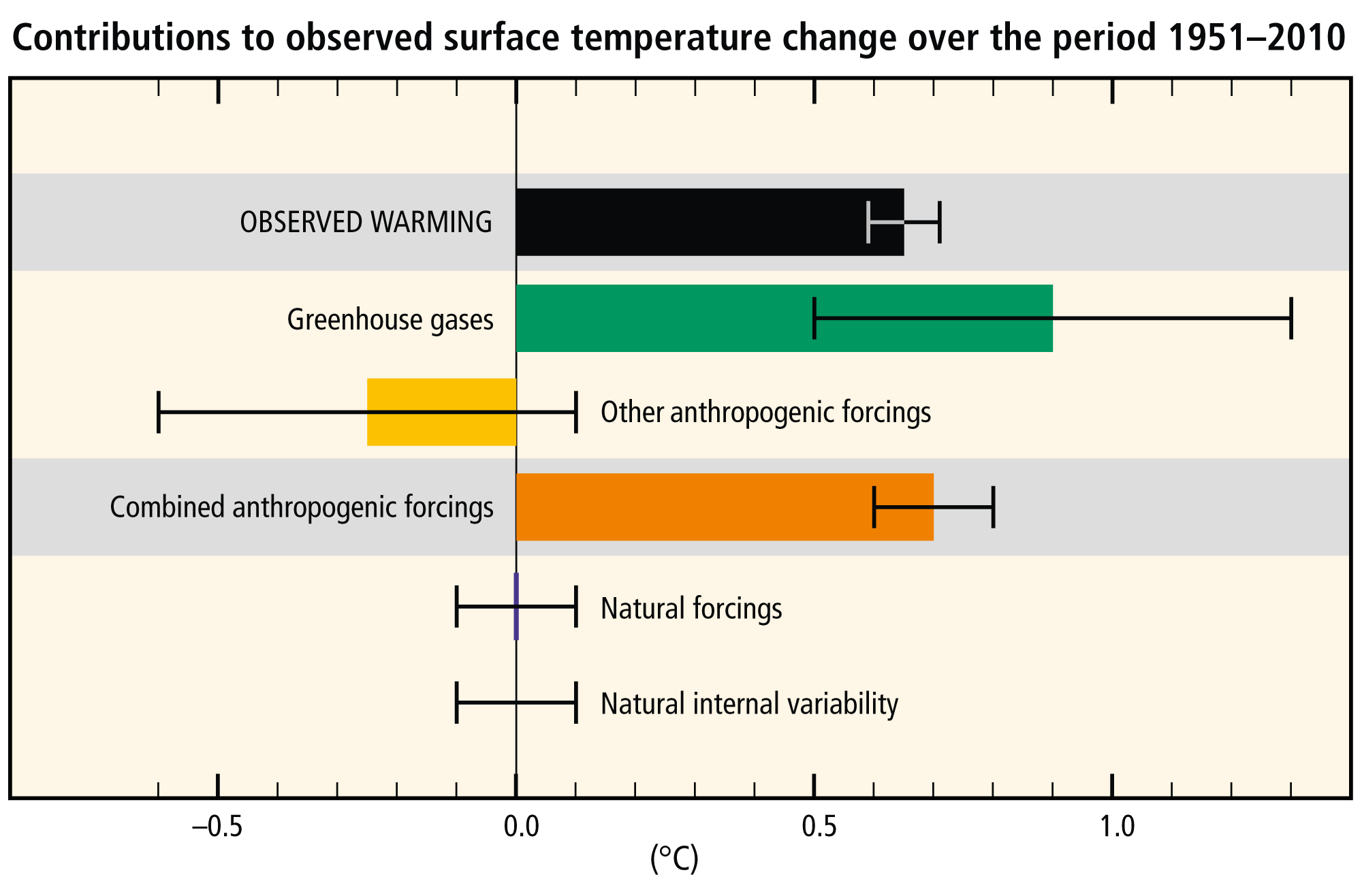

The evidence for human influence on the climate system has grown since the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4). It is extremely likely that more than half of the observed increase in global average surface temperature from 1951 to 2010 was caused by the anthropogenic increase in GHG concentrations and other anthropogenic forcings together. The best estimate of the human-induced contribution to warming is similar to the observed warming over this period (Figure SPM.3). Anthropogenic forcings have likely made a substantial contribution to surface temperature increases since the mid-20th century over every continental region except Antarctica4. Anthropogenic influences have likely affected the global water cycle since 1960 and contributed to the retreat of glaciers since the 1960s and to the increased surface melting of the Greenland ice sheet since 1993. Anthropogenic influences have very likely contributed to Arctic sea-ice loss since 1979 and have very likely made a substantial contribution to increases in global upper ocean heat content (0–700 m) and to global mean sea level rise observed since the 1970s. {1.3, Figure 1.10}

EditFigure SPM.3 | Assessed likely ranges (whiskers) and their mid-points (bars) for warming trends over the 1951–2010 period from well-mixed greenhouse gases, other anthropogenic forcings (including the cooling effect of aerosols and the effect of land use change), combined anthropogenic forcings, natural forcings, and natural internal climate variability (which is the element of climate variability that arises spontaneously within the climate system even in the absence of forcings). The observed surface temperature change is shown in black, with the 5 to 95% uncertainty range due to observational uncertainty. The attributed warming ranges (colours) are based on observations combined with climate model simulations, in order to estimate the contribution of an individual external forcing to the observed warming. The contribution from the combined anthropogenic forcings can be estimated with less uncertainty than the contributions from greenhouse gases and from other anthropogenic forcings separately. This is because these two contributions partially compensate, resulting in a combined signal that is better constrained by observations. {Figure 1.9}

SPM.1.3. Impacts of climate change

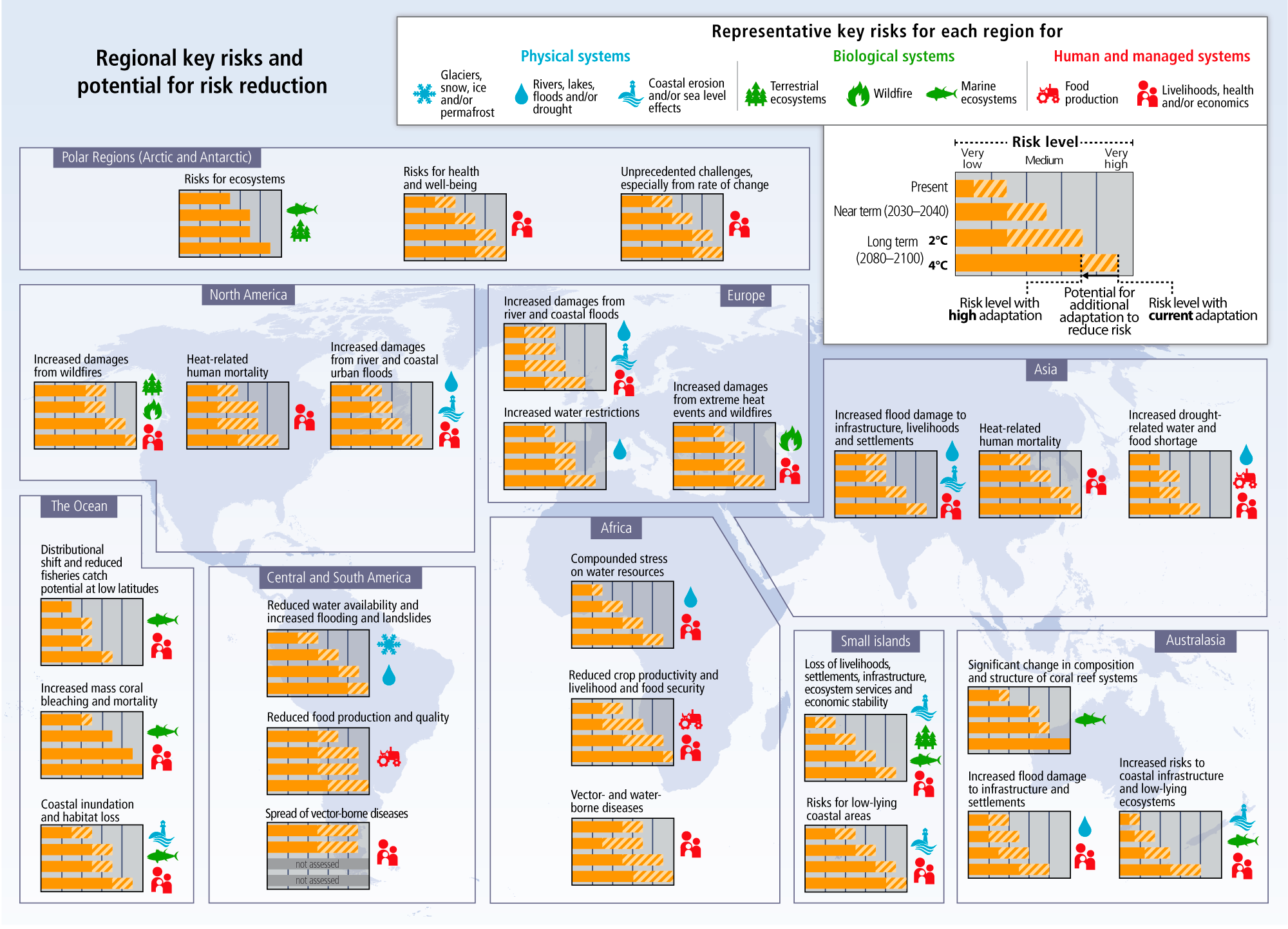

In recent decades, changes in climate have caused impacts on natural and human systems on all continents and across the oceans. Impacts are due to observed climate change, irrespective of its cause, indicating the sensitivity of natural and human systems to changing climate. {1.3.2}

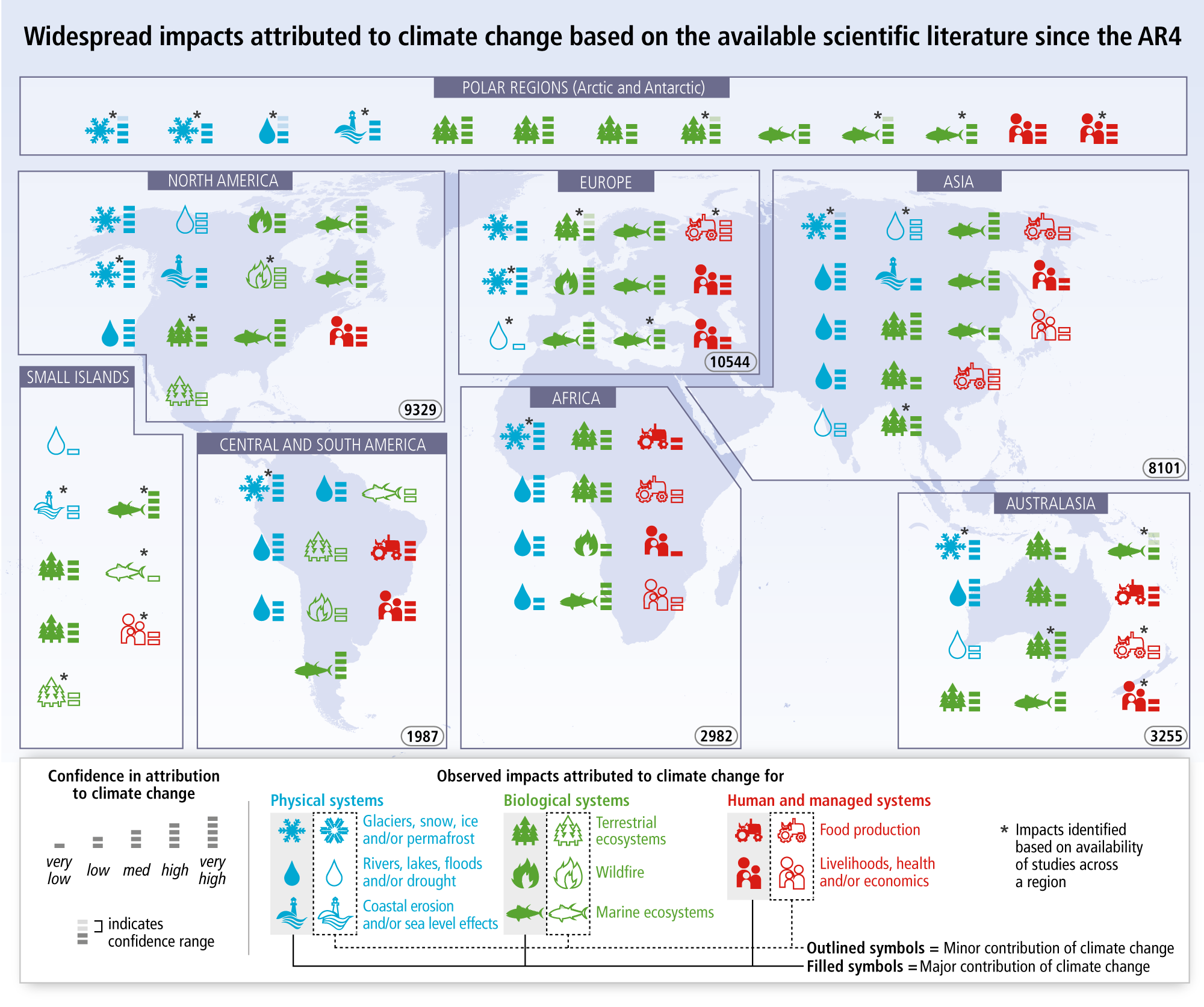

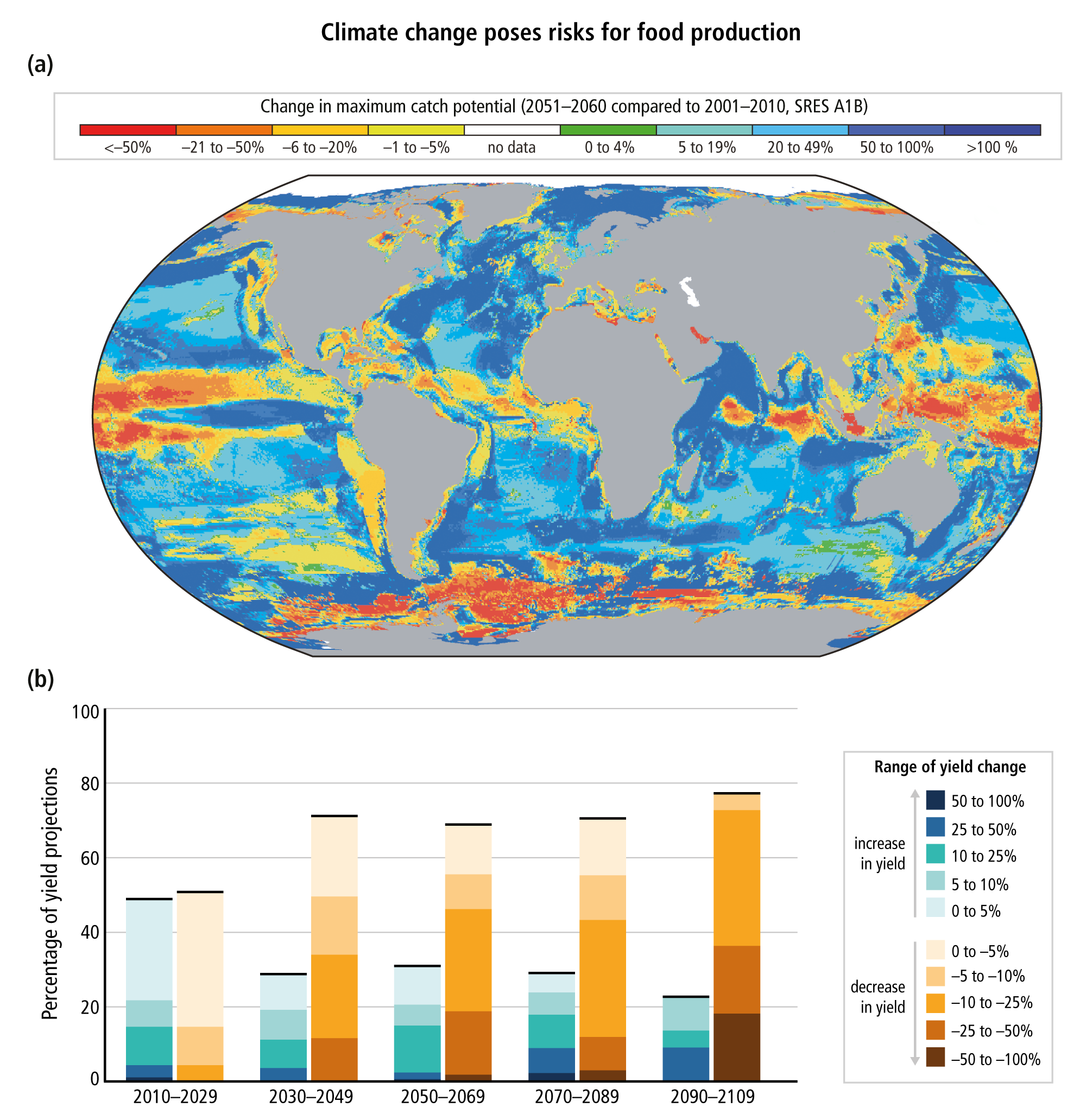

Evidence of observed climate change impacts is strongest and most comprehensive for natural systems. In many regions, changing precipitation or melting snow and ice are altering hydrological systems, affecting water resources in terms of quantity and quality (medium confidence). Many terrestrial, freshwater and marine species have shifted their geographic ranges, seasonal activities, migration patterns, abundances and species interactions in response to ongoing climate change (high confidence). Some impacts on human systems have also been attributed to climate change, with a major or minor contribution of climate change distinguishable from other influences (Figure SPM.4). Assessment of many studies covering a wide range of regions and crops shows that negative impacts of climate change on crop yields have been more common than positive impacts (high confidence). Some impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms have been attributed to human influence (medium confidence). {1.3.2}

EditFigure SPM.4 | Based on the available scientific literature since the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report AR4, there are substantially more impacts in recent decades now attributed to climate change. Attribution requires defined scientific evidence on the role of climate change. Absence from the map of additional impacts attributed to climate change does not imply that such impacts have not occurred. The publications supporting attributed impacts reflect a growing knowledge base, but publications are still limited for many regions, systems and processes, highlighting gaps in data and studies. Symbols indicate categories of attributed impacts, the relative contribution of climate change (major or minor) to the observed impact and confidence in attribution. Each symbol refers to one or more entries in WGII Table SPM.A1, grouping related regional-scale impacts. Numbers in ovals indicate regional totals of climate change publications from 2001 to 2010, based on the Scopus bibliographic database for publications in English with individual countries mentioned in title, abstract or key words (as of July 2011). These numbers provide an overall measure of the available scientific literature on climate change across regions; they do not indicate the number of publications supporting attribution of climate change impacts in each region. Studies for polar regions and small islands are grouped with neighbouring continental regions. The inclusion of publications for assessment of attribution followed IPCC scientific evidence criteria defined in WGII Chapter 18. Publications considered in the attribution analyses come from a broader range of literature assessed in the WGII AR5. See WGII Table SPM.A1 for descriptions of the attributed impacts. {Figure 1.11}

SPM.1.4. Extreme events

Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950. Some of these changes have been linked to human influences, including a decrease in cold temperature extremes, an increase in warm temperature extremes, an increase in extreme high sea levels and an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events in a number of regions. {1.4}

It is very likely that the number of cold days and nights has decreased and the number of warm days and nights has increased on the global scale. It is likely that the frequency of heat waves has increased in large parts of Europe, Asia and Australia. It is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed global scale changes in the frequency and intensity of daily temperature extremes since the mid-20th century. It is likely that human influence has more than doubled the probability of occurrence of heat waves in some locations. There is medium confidence that the observed warming has increased heat-related human mortality and decreased cold-related human mortality in some regions. {1.4}

There are likely more land regions where the number of heavy precipitation events has increased than where it has decreased. Recent detection of increasing trends in extreme precipitation and discharge in some catchments implies greater risks of flooding at regional scale (medium confidence). It is likely that extreme sea levels (for example, as experienced in storm surges) have increased since 1970, being mainly a result of rising mean sea level. {1.4}

Impacts from recent climate-related extremes, such as heat waves, droughts, floods, cyclones, and wildfires, reveal significant vulnerability and exposure of some ecosystems and many human systems to current climate variability (very high confidence). {1.4}

Edit